Behavior, Automatic Reinforcement, and Rudolph’s Red Nose

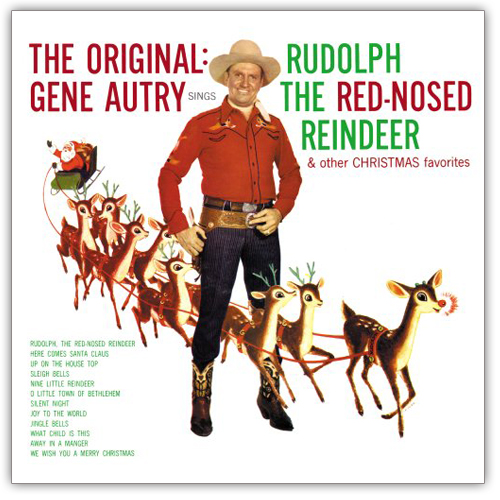

The legend of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer was revealed in 1939 by Robert L. May. It went truly viral when cowboy/singer Gene Autrey first recorded that song we all know, in 1949. Never answered, however, was why that Most Famous Reindeer of All’s nose was red in the first place. Some have speculated about capillary development around the nasal cavity and even the evolution of bioluminescent organs. One ugly rumor I have heard is that resulted from excessive imbibing. We won’t go there. Never has it been proposed that the redness of Rudolph’s nose is an instance of operant behavior, the kind of behavior that the science of behavior analysis addresses in depth. Until now.

The legend of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer was revealed in 1939 by Robert L. May. It went truly viral when cowboy/singer Gene Autrey first recorded that song we all know, in 1949. Never answered, however, was why that Most Famous Reindeer of All’s nose was red in the first place. Some have speculated about capillary development around the nasal cavity and even the evolution of bioluminescent organs. One ugly rumor I have heard is that resulted from excessive imbibing. We won’t go there. Never has it been proposed that the redness of Rudolph’s nose is an instance of operant behavior, the kind of behavior that the science of behavior analysis addresses in depth. Until now.

Could it be?

To answer this question, we need to consider two others: First, what is operant behavior? And, if we can establish that redness can be operant behavior, what is the reinforcer maintaining it?

Let’s assume first that redness is a physiological reaction, like many others mediated by the autonomic nervous system (ANS). The ANS controls our “fight or flight” responses. Can an ANS response be an operant behavior? Operant behavior is behavior controlled by its consequences. It was discovered by B.F. Skinner, who considered it distinct from the conditioned reflex, discovered earlier by Ivan Pavlov. Before the 1960s, a distinction sometimes made between the two types of behavior was that operant behavior involved using the long muscles of the body and reflexive behavior involved the smooth muscles of the  internal organs, which are in turn controlled by the ANS. By the 1960s, this distinction was no longer tenable, largely, but not exclusively, because of several demonstrations (some since seriously questioned, but others holding up under varying degrees of scientific scrutiny) that the smooth muscles of the body could serve as the basis for operant conditioning. These demonstrations became the scientific basis for biofeedback, something that remains an important tool today in clinical and medical psychology. For example, using biofeedback in the form of a digital readout of blood pressure a person with high blood pressure can learn to lower their blood pressure. If we consider redness as a physiological response, and physiological responses can be affected by their consequences, it follows that the redness of Rudolph’s nose could be operant behavior.

internal organs, which are in turn controlled by the ANS. By the 1960s, this distinction was no longer tenable, largely, but not exclusively, because of several demonstrations (some since seriously questioned, but others holding up under varying degrees of scientific scrutiny) that the smooth muscles of the body could serve as the basis for operant conditioning. These demonstrations became the scientific basis for biofeedback, something that remains an important tool today in clinical and medical psychology. For example, using biofeedback in the form of a digital readout of blood pressure a person with high blood pressure can learn to lower their blood pressure. If we consider redness as a physiological response, and physiological responses can be affected by their consequences, it follows that the redness of Rudolph’s nose could be operant behavior.

If Rudolph’s red nose indeed is operant behavior, then the next question is how is it maintained? What can reinforce a nose turning, and then staying, red? To answer this question actually would require an experiment, which in turn would require the (apparently) one and only red-nosed reindeer. Since that ain’t gonna happen (no way Santa would give up his chief guide-deer just before Christmas …or any other time if he is half as smart as I suspect him to be – that red-nosed franchise is worth a fortune), I am forced to speculate. So I will.

If Rudolph’s red nose indeed is operant behavior, then the next question is how is it maintained? What can reinforce a nose turning, and then staying, red? To answer this question actually would require an experiment, which in turn would require the (apparently) one and only red-nosed reindeer. Since that ain’t gonna happen (no way Santa would give up his chief guide-deer just before Christmas …or any other time if he is half as smart as I suspect him to be – that red-nosed franchise is worth a fortune), I am forced to speculate. So I will.

The idea of automatic reinforcement was first proposed by Skinner in the 1950s. He suggested that some behavior is in itself reinforcing, just by its occurrence. Automatic reinforcement has been used to account for some instances of serious problem behavior such as self-injurious and repetitive stereotyped behavior of various sorts (e.g. aimless pacing around, tic-like behavior, even forms of compulsive behavior). The merits and drawbacks of automatic reinforcement are beyond what I can present here. Suffice to say that many behavior analysts are skeptical of reinforcers they can’t see. As a die-hard empiricist, I confess to falling in this latter group.

The idea of automatic reinforcement was first proposed by Skinner in the 1950s. He suggested that some behavior is in itself reinforcing, just by its occurrence. Automatic reinforcement has been used to account for some instances of serious problem behavior such as self-injurious and repetitive stereotyped behavior of various sorts (e.g. aimless pacing around, tic-like behavior, even forms of compulsive behavior). The merits and drawbacks of automatic reinforcement are beyond what I can present here. Suffice to say that many behavior analysts are skeptical of reinforcers they can’t see. As a die-hard empiricist, I confess to falling in this latter group.

But, hey, this is the season for believing in things unseen, is it not? Therefore, in the spirit of the season, I am willing to let go of my biases and consider the possibility that maybe Rudolph’s red nose, which we established above could be an instance of operant behavior, is maintained by automatic reinforcement. Next, we’ll tackle the tooth fairy.

Until then, during this season of peace, may your reinforcers be frequent and punishers rare. Best wishes for the holidays from The Aubrey Daniels Institute.