An Experimental Life

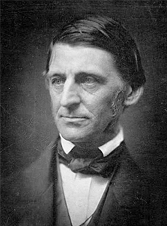

Ralph Waldo Emerson said, “Do not be too timid and squeamish about your actions. All life is an experiment.” For most of my adult life I have been in the enviable position of being able to do that every day in my life’s work. As a teacher, I have the privilege of working with very bright and capable students, both undergraduate and graduate, exploring the origins and causes of behavior. The work being experimental in nature, we consider ourselves to be in a truly exciting place, on the cutting edge of new knowledge with the opportunity to go, to paraphrase that famous line from Stark Trek, where no one has been before. Because we are going to that place, there is no well-trodden path and sometimes not even guidelines as to how to navigate our way. And that’s the fun of it.

Ralph Waldo Emerson said, “Do not be too timid and squeamish about your actions. All life is an experiment.” For most of my adult life I have been in the enviable position of being able to do that every day in my life’s work. As a teacher, I have the privilege of working with very bright and capable students, both undergraduate and graduate, exploring the origins and causes of behavior. The work being experimental in nature, we consider ourselves to be in a truly exciting place, on the cutting edge of new knowledge with the opportunity to go, to paraphrase that famous line from Stark Trek, where no one has been before. Because we are going to that place, there is no well-trodden path and sometimes not even guidelines as to how to navigate our way. And that’s the fun of it.

Our work involves frequent, lively discussions about how to study a particular problem or phenomenon of behavior. I have observed two common themes across many such discussions with my students. First, they often look to me first for guidance as to what to do. I am, after all, their teacher. Second, we, together through exciting dialogue, weigh different approaches, speculating about the possible outcomes and implications of trying various procedures in our behavioral experiments.

Being a teacher is like being a guide, but when the territory is unexplored, any guide must be guided by his or her past experiences (something we often call “intuitions,” but which, as I have noted in an earlier commentary, really are observations governed by past experiences). So, my guidance isn’t, as I well know, and indeed, can’t be, perfect. Quite reasonably, they ask me for the answers to the questions they have along the way. But my job is in great part to help them develop their own experience base. I do have some ideas about how to navigate, based on my years of experience in behavioral research. Sometimes my intuitions are right on, but at other times they turn out to be dead ends. Not surprising to me, but not something my students expect. When this happens, I remind them of the journey to new discovery we are all on, where we are at this moment and the nature of our activity. They come to understand I am, like them, seeking to know.

Talking about our work together is very stimulating, and the source of many new ideas for further explorations. Our discussions often are exciting and animated, with lots of drawings of diagrams and wild speculation about “what ifs” and the implications of one outcome versus another. At the end of the day, though, we often are not sure how to proceed. There sometimes is considerable handwringing and gnashing of teeth as to which path to take. It’s at this point that I remind them that “it’s an experiment” and if we knew the answer there would be no point in doing the experiment in the first place. So, I say, let’s try something and see what happens. The worst outcome is that we learn something interesting, even if it isn’t what we thought it would be. The best outcome is that we were right and we have confirmed experimentally our more causal observations made in the absence of data.

I remind students, and myself, that, like our work at the university, our lives are experiments. We don’t know the path, but have to base our journey on what we do know or have intuitions about. We don’t know how certain adventures or their absence will affect us and the only way to find out is to try them and see…or not. The outcomes sometimes work for us and sometimes not, but we always learn from them. We are our experiences combined with the present circumstance in which we find ourselves. Admittedly, in my personal life I am not always as good as Emerson might ask of me or my life’s work would teach me, but when I remember to look at life as an experiment, with all its pitfalls and possibilities, I understand that I can venture out and take the measured risks of living life to the fullest, keeping my eyes open to both intended and unintended effects in this grand experiment. And then redesign and try again.