Fifty Shades of Behavior-Analytic Grey

Charles Darwin’s insights about the origin of species were based on his observations concerning the relation of selection and variation to change. The variations among individuals allowed selection to occur. If there is no variation, there is nothing to select from because everything is the same. When variation among members of a species is large, changes in the environment, such as a change in the availability of certain foods, usually can be accommodated by at least some members of a species. When variation narrows so that all members of a species are more or less alike, the species becomes more vulnerable to extinction. A change in the availability of the foods mentioned above now becomes a bigger problem, because very few or maybe even none of the species members can digest any other food. The result is that large numbers die off, making it difficult for the species to survive. This Darwinian homily has implications for our science of behavior analysis.

Within behavior analysis, there are “orthodox” or “fundamentalist” behavior analysts who defer to the ideas of Skinner in defining the conceptual underpinnings of our discipline. There also are what we might call “reformist” behavior analysts who take the tact that Skinner has provided a firm foundation of conceptual underpinnings, but these underpinnings are open to reinterpretation and change. As for specific ideas themselves, there is plenty of variation. Take private events, for example. Some people believe strongly that they have a place in behavior analysis, at least conceptually, and others would like to have them excluded from consideration in constructing a science of behavior. Many other card-carrying behavior analysts fall between these two extremes. Some behavior analysts would like to learn the “truth” about private events, others are more circumspect and open to the point of view that there is no real answer to the question. Another example is the so-called molar-molecular controversy: whether reinforcement has its effects because of moment to moment temporal contiguities between responses and reinforcers that follow or because of the integration of reinforcers and responses across more extended time frames.

Aside from the “fact” that there are no fast and firm answers to many of the epistemological and experimental questions posed within a behavior-analytic world view, there is great value, often seemingly unrecognized, in the variation among people in their understanding of the basic tenants of our discipline. The reason, of course, harks back to the principles of variation and selection. If we all believe exactly the same thing, then the discipline cannot change and we are forever stuck in mid-20th century ideas of what behavior analysis was and is. This seems terribly counterproductive and, indeed, dangerous to the survival of our discipline. Without a range of viable ideas about private events or any other topic that concerns behavior analysts, we???? Most significantly, such a lack of variation would doom our disciple to stagnation, if not extinction.

Behavior analysis often is described as a pragmatic, solution-oriented science, whether the goal is advancing the understanding of behavior or treating behavior. Ideas that lead to variations worthy of consideration often come from the work of others outside our field. Failing to acknowledge that disciplines other than our own might have something worthwhile to offer or devaluing the contributions they have made violates our own pragmatic orientation. Considering the data and outcomes that these other disciplines have achieved, without accepting their explanations as to why the achievements have happened, seems a more useful, and productive, approach for behavior analysis.

Behavior analysis often is described as a pragmatic, solution-oriented science, whether the goal is advancing the understanding of behavior or treating behavior. Ideas that lead to variations worthy of consideration often come from the work of others outside our field. Failing to acknowledge that disciplines other than our own might have something worthwhile to offer or devaluing the contributions they have made violates our own pragmatic orientation. Considering the data and outcomes that these other disciplines have achieved, without accepting their explanations as to why the achievements have happened, seems a more useful, and productive, approach for behavior analysis.

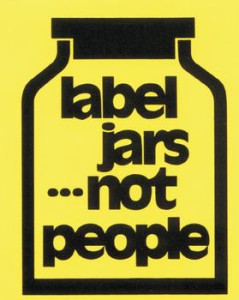

Some behavior analysts sometimes seem too quick to label some of our own colleagues who respond to new advances and other explanations outside the behavioral liturgy of what is appropriate as “real” or “not real” behavior analysts. Such labeling disallows variation from our own particular view of what the discipline, and answers to questions about behavior. The effects of such orthodoxy aren’t in the best interest of our discipline. Orthodoxy creates an elite group that further insulates and separates from both other behavior analysts and the broader community of scientists and practitioners who share our concern with understanding behavior.

Some behavior analysts sometimes seem too quick to label some of our own colleagues who respond to new advances and other explanations outside the behavioral liturgy of what is appropriate as “real” or “not real” behavior analysts. Such labeling disallows variation from our own particular view of what the discipline, and answers to questions about behavior. The effects of such orthodoxy aren’t in the best interest of our discipline. Orthodoxy creates an elite group that further insulates and separates from both other behavior analysts and the broader community of scientists and practitioners who share our concern with understanding behavior.