B. F. Skinner’s Lost Twin Brother

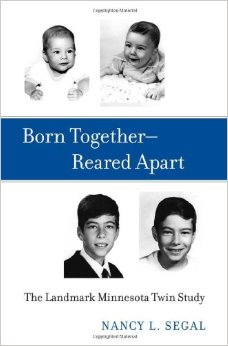

B. F. Skinner’s first academic position was at the University of Minnesota in the late 1930s. It is generally acknowledged that his research changed the face of modern psychology. Roughly four decades later, what has become known as the University of Minnesota Twin Studies changed our understanding of the world of identical twins. Based on studies of such twins separated at birth raised apart, quite amazing behavioral similarities despite often quite totally different environmental influences were revealed when these twins were found and interviewed as adults. Now it can be known that there is an ironic connection between Skinner and this project.

B. F. Skinner’s first academic position was at the University of Minnesota in the late 1930s. It is generally acknowledged that his research changed the face of modern psychology. Roughly four decades later, what has become known as the University of Minnesota Twin Studies changed our understanding of the world of identical twins. Based on studies of such twins separated at birth raised apart, quite amazing behavioral similarities despite often quite totally different environmental influences were revealed when these twins were found and interviewed as adults. Now it can be known that there is an ironic connection between Skinner and this project.

When Skinner left Minnesota in the early 1940s to become Department Chair at Indiana University, he left behind in his laboratory a Skinner family bible that somehow found its way into the University Archives. The bible apparently remained unopened until one day recently when quite by accident a postdoctoral fellow involved with the twins project looking for something else in the Archives happened upon it. As he began thumbing through it, he first found a note from Skinner tucked just under the cover. It indicated the bible’s history and, for reasons unknown, stated that he (Skinner) had never once in his life opened the bible beyond placing this note under the cover. Further into the bible, on the page recording births and deaths, there was a stunning revelation, later verified by the Twins Project staff.

When Skinner left Minnesota in the early 1940s to become Department Chair at Indiana University, he left behind in his laboratory a Skinner family bible that somehow found its way into the University Archives. The bible apparently remained unopened until one day recently when quite by accident a postdoctoral fellow involved with the twins project looking for something else in the Archives happened upon it. As he began thumbing through it, he first found a note from Skinner tucked just under the cover. It indicated the bible’s history and, for reasons unknown, stated that he (Skinner) had never once in his life opened the bible beyond placing this note under the cover. Further into the bible, on the page recording births and deaths, there was a stunning revelation, later verified by the Twins Project staff.

The world can now know that B. F. Skinner’s mother gave birth to identical twin boys on March 20, 1904. For reasons that remain murky, one of the twins was lost by the hospital almost immediately after the birth. The loss created such grief that the so-called Lost Twin was never discussed by Skinner’s parents, not even with their remaining twin son.

The world can now know that B. F. Skinner’s mother gave birth to identical twin boys on March 20, 1904. For reasons that remain murky, one of the twins was lost by the hospital almost immediately after the birth. The loss created such grief that the so-called Lost Twin was never discussed by Skinner’s parents, not even with their remaining twin son.

The Lost Twin, as he will be known to future generations, through some unknown means was mistakenly taken to Finland where he was put up for adoption. A man and a woman named Nahkuri adopted the boy at about two months of age and raised him in a small village about 40 kilometers from Helsinki. They named him Johannes, after his adopted mother’s father. From the few available reports of his early life, we have learned that Johannes was greatly loved and developed into an inquisitive and intelligent boy. He was, for example, forever tinkering with gadgets, making fantastic contraptions to ease his mother’s and father’s work.

Fast forward to November 30, 1939, when Finland began fighting for its survival following the commencement of an invasion by the Soviet Union on that date. The armed struggle that followed became known as the Winter War. The greatly outnumbered Finnish forces fought tenaciously and held back the Soviets briefly before the Red Army redoubled its efforts. A few months before, with this very invasion weighing heavily on the Finnish people, we find Johannes (the resemblance to Skinner is remarkable, but such is the fate of identical twins), now a doctoral candidate in psychology at the University of Helsinki, sitting at a bar in Helsinki with his older brother, Erkki, the natural son of the Nahkuris, Erkki was an engineer deeply involved in what to that point was an unsuccessful project to develop a guidance system for an unmanned glider bomb that, if successful, could well turn the tide of the anticipated Soviet invasion. Over the course of the evening (how interesting would it have been to be a fly on the wall in that bar on that evening?) and the consumption of copious amounts of alcohol, Erkki and Johannes developed a truly strange alternative plan for the guidance system of the unmanned bomber.

Fast forward to November 30, 1939, when Finland began fighting for its survival following the commencement of an invasion by the Soviet Union on that date. The armed struggle that followed became known as the Winter War. The greatly outnumbered Finnish forces fought tenaciously and held back the Soviets briefly before the Red Army redoubled its efforts. A few months before, with this very invasion weighing heavily on the Finnish people, we find Johannes (the resemblance to Skinner is remarkable, but such is the fate of identical twins), now a doctoral candidate in psychology at the University of Helsinki, sitting at a bar in Helsinki with his older brother, Erkki, the natural son of the Nahkuris, Erkki was an engineer deeply involved in what to that point was an unsuccessful project to develop a guidance system for an unmanned glider bomb that, if successful, could well turn the tide of the anticipated Soviet invasion. Over the course of the evening (how interesting would it have been to be a fly on the wall in that bar on that evening?) and the consumption of copious amounts of alcohol, Erkki and Johannes developed a truly strange alternative plan for the guidance system of the unmanned bomber.

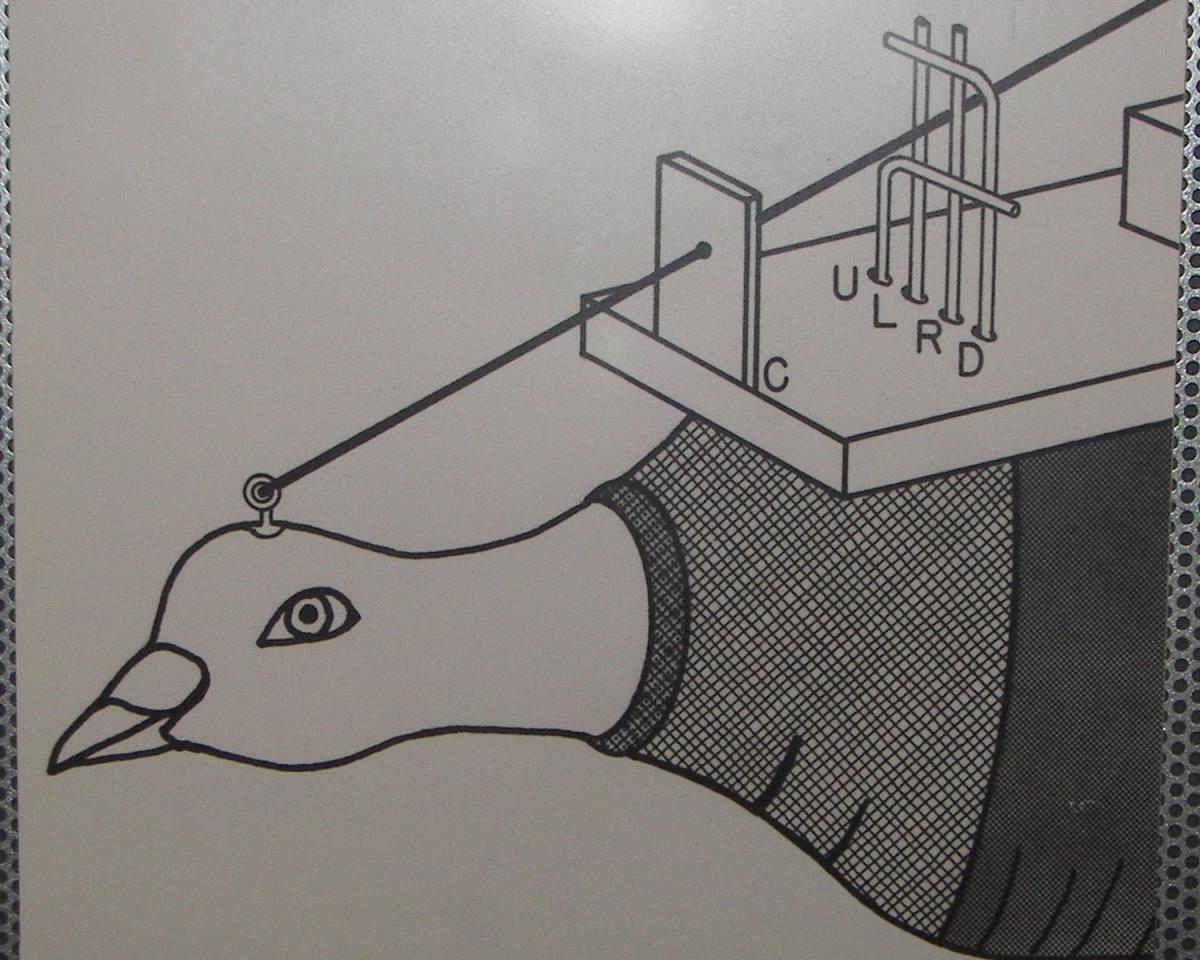

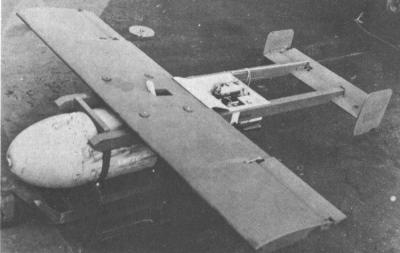

Johannes, who was conducting his doctoral dissertation on learning with pigeons, proposed changing the glider bomb’s guidance system to one controlled by pigeons. Within a very short period of time following their recovery from the colossal hangover induced by the aforementioned overindulgence, Johannes had redirected his efforts to the guidance system, developing a technique of target monitoring in which the pigeon learned to keep a moving target on the crosshairs of a sight by pecking a series of response keys placed in a diamond shape and connected to electrical circuitry. If, for example, the pigeon pecked the upper key, the circuitry moved the crosshairs down, if it pecked the left key, the crosshairs moved to the right, and so on. An illustration of how the device translated head movements into crosshair movements is shown here. Within a couple of months, Johannes had perfected the system. In another six weeks (the Finnish bureaucracy is no different than that anywhere else in the world), the first “live” tests were conducted. A week later the system was operational. By this time it was early December and the Finnish army was struggling to defend its country against the several-fold larger Red Army. By mid-December, the first pigeons from Johannes Nahkuri’s laboratory were loaded into the Lintu-Liito-Pommi Malli-40 (Bird Glide Bomb Model 40).

Johannes, who was conducting his doctoral dissertation on learning with pigeons, proposed changing the glider bomb’s guidance system to one controlled by pigeons. Within a very short period of time following their recovery from the colossal hangover induced by the aforementioned overindulgence, Johannes had redirected his efforts to the guidance system, developing a technique of target monitoring in which the pigeon learned to keep a moving target on the crosshairs of a sight by pecking a series of response keys placed in a diamond shape and connected to electrical circuitry. If, for example, the pigeon pecked the upper key, the circuitry moved the crosshairs down, if it pecked the left key, the crosshairs moved to the right, and so on. An illustration of how the device translated head movements into crosshair movements is shown here. Within a couple of months, Johannes had perfected the system. In another six weeks (the Finnish bureaucracy is no different than that anywhere else in the world), the first “live” tests were conducted. A week later the system was operational. By this time it was early December and the Finnish army was struggling to defend its country against the several-fold larger Red Army. By mid-December, the first pigeons from Johannes Nahkuri’s laboratory were loaded into the Lintu-Liito-Pommi Malli-40 (Bird Glide Bomb Model 40).

The LLP/ms were an immediate tactical success on the battlefields of Finland. On the 14th of December 1939, the pigeon-guided bombs destroyed two SovietNavy destroyers that were attacking the lighthouse and fortifications at Utö.

The Soviet destroyer Gnevny blown into two pieces by a pigeon-guided LLP/m 40

The LLP/m 40s thereafter were used against Soviet tanks with equal success. They also played a major role in routing the Soviets in the Red Army’s last attack on the Mannerheim Line in March, 1940.

A combination of Hitler turning his military might on the Soviet Union from its southern flanks and the fear induced in the Red Army leadership by the devastating effects of the LLP/m 40s resulted in a Soviet withdrawal and a period of relative peace along the Finnish-Soviet border that held for the remainder of the war. With the invasion threat ebbed, Johannes returned to the University to complete his degree and become an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at the University.

Only when World War II ended did the Finnish government reveal its top secret LLP/m40 project. A few months thereafter, it recognized Johannes Nahkuri’s contributions to ending the Winter War with a painting of him, still on display today at the Helsinki Museum of Art. Not surprisingly, Nahkuri is holding a pigeon in front of an LLP/m40 nose cone. The toll of the war is apparent from his appearance, for his war efforts aged him considerably.

Footnote to this remarkable story: Tragically, Johannes Nahkuri did not live to receive the accolades bestowed upon him by his government and the Finnish people. Only three days following the formal end of the War in Europe, Johannes met his maker while attempting to place a pigeon in what is now known as an operant conditioning chamber. It was located on a high shelf in his laboratory. The chamber was constructed of an especially heavy material designed to minimize outside noise penetrating into the chamber. As he placed a pigeon in the chamber, he slipped off of the ladder on which he was standing and grabbed the edge of the chamber door, pulling it onto him as he fell. He was unmarried. His adopted parents and brother both died during the Winter War, leaving no relatives in Finland. Doubly sadly, because his twin brother Fred never opened the family bible, both he and his twin brother died without ever having known that they had a twin.

Footnote to this remarkable story: Tragically, Johannes Nahkuri did not live to receive the accolades bestowed upon him by his government and the Finnish people. Only three days following the formal end of the War in Europe, Johannes met his maker while attempting to place a pigeon in what is now known as an operant conditioning chamber. It was located on a high shelf in his laboratory. The chamber was constructed of an especially heavy material designed to minimize outside noise penetrating into the chamber. As he placed a pigeon in the chamber, he slipped off of the ladder on which he was standing and grabbed the edge of the chamber door, pulling it onto him as he fell. He was unmarried. His adopted parents and brother both died during the Winter War, leaving no relatives in Finland. Doubly sadly, because his twin brother Fred never opened the family bible, both he and his twin brother died without ever having known that they had a twin.

The Minnesota Twin Project revealed many remarkable behavioral similarities between twins separated at birth and never encountering one another until much later in life. It therefore is not totally surprising that these two talented twins invented similar weapons systems when their country called. Remarkable though the similarities are between Nahkuri’s (nee Skinner) LLP/m40 project and Skinner’s Project Pelican, there is one major difference: Fred’s project was never given an operational test, but his twin brother Johannes’s saved Finland from becoming another Soviet satellite.

The Minnesota Twin Project revealed many remarkable behavioral similarities between twins separated at birth and never encountering one another until much later in life. It therefore is not totally surprising that these two talented twins invented similar weapons systems when their country called. Remarkable though the similarities are between Nahkuri’s (nee Skinner) LLP/m40 project and Skinner’s Project Pelican, there is one major difference: Fred’s project was never given an operational test, but his twin brother Johannes’s saved Finland from becoming another Soviet satellite.

For a far more detailed history of this project (which, now that it is out will rewrite history of psychology textbooks worldwide) and its role in the Winter War visit, Axis History Forum, and scroll down to “The most heavily armed pigeons in the world, part III,” which is the basis of much of this tale.

And, by the way, April Fool from the Aubrey Daniels Institute.