In our media-intense universe, news about industrial catastrophes reaches us within minutes. We may tell ourselves that though such incidents are tragic, at least industrial safety has progressed by light years over past decades and accidents resulting in deaths are fewer. We may even harbor a false sense of security that government oversight and corporate proclamations of safety as a first priority will mitigate the dangers of the workplace. Some of these viewpoints may be partially justifiable, but according to behavioral safety specialist, Dr. Dwight Harshbarger, the past predicts the present, serving as a dire warning against complacency.

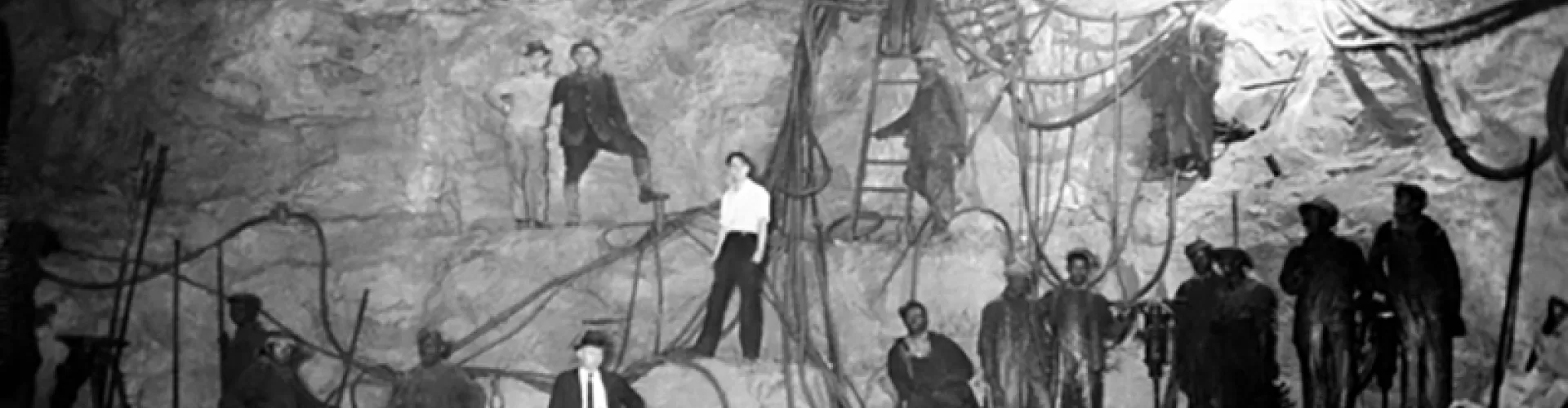

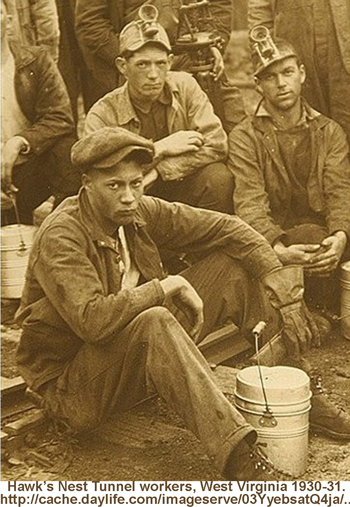

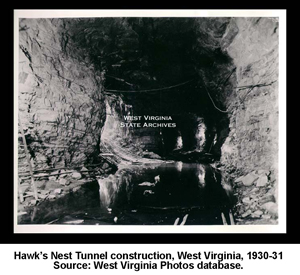

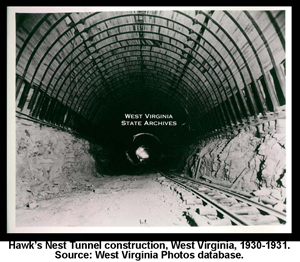

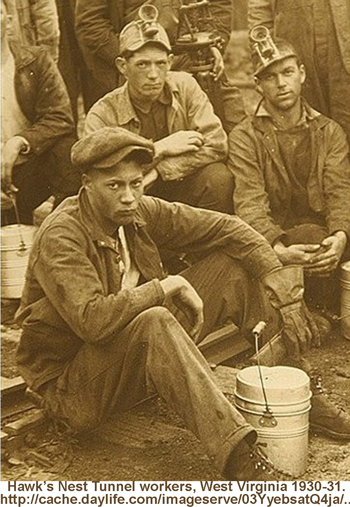

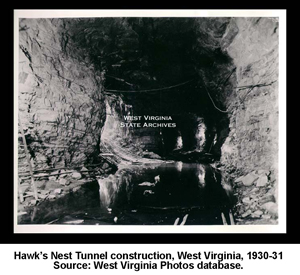

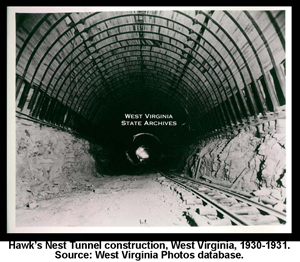

In his many years working with business and industry, specializing in strengthening quality and safety performance in organizations, Harshbarger has heard many tales of dangerous worksites, but one story of corporate neglect and hubris from years ago continued to haunt him—that of Hawks Nest tunnel—in his home state of West Virginia. There, in the financially troubled 1930s, Union Carbide and Carbon Corporation enlisted the service of desperate men, those willing to work for 25 cents per day, most of them black, and all of them poverty stricken. Their charge was to dig a three-mile-long tunnel through Gauley Mountain to channel the energy-making powers of the New River to generate electricity for Union Carbide’s factories.

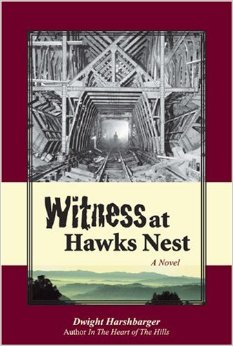

In a completely avoidable disaster, at least 764 men subsequently died agonizing deaths of the lung disease, silicosis. Some accounts report that as many as 1200 perished, but the number is difficult to ascertain since the company secreted the men’s corpses in remote and remorseless graves. Now recorded as the worst industrial disaster in U. S. history, this inhumane event was successfully hidden from the American public by both big business and government entities. This is the story told by Harshbarger in his novel Witness at Hawks Nest. Based on true, horrific, yet historically accurate events, the novel exposes the results that can unfold from behaviors driven by callousness, irresponsibility, and profit-focused greed.

In a completely avoidable disaster, at least 764 men subsequently died agonizing deaths of the lung disease, silicosis. Some accounts report that as many as 1200 perished, but the number is difficult to ascertain since the company secreted the men’s corpses in remote and remorseless graves. Now recorded as the worst industrial disaster in U. S. history, this inhumane event was successfully hidden from the American public by both big business and government entities. This is the story told by Harshbarger in his novel Witness at Hawks Nest. Based on true, horrific, yet historically accurate events, the novel exposes the results that can unfold from behaviors driven by callousness, irresponsibility, and profit-focused greed.

Harshbarger, with this second novel, states that he is making the gradual transition from consulting and teaching to the “tough taskmaster” of writing. In this interview, he shares his insights on the Hawks Nest incident and its implications for current safety managers and professionals.

Why did you decide to write the Hawks Nest story in novel form as opposed to nonfiction?

There is a nonfiction treatment of the disaster called The Hawk’s Nest Incident: America’s Worst Industrial Disaster by Martin Cherniack. Martin is an epidemiologist and a physician but he’s also kind of an amateur historian, and a good one. His historical account of the tunnel and deaths and silicosis is unbelievably thorough and deeply researched, so there’s really no need for another one of those. The first novel about the incident was written by Hubert Skidmore, published in 1941 by Doubleday, and reviewed in the NY Times. One year later it had been forced off the market. The novel was republished in 2005 by the University of Tennessee Press.

How is your novel different from Skidmore’s novel?

Skidmore’s novel is an account from the point of view of three men who are working inside the tunnel and what happens to those men when they find themselves becoming short of breath and unable to do the things they like to do. My perspective is more one of how decisions were made, decisions that ended up killing hundreds and hundreds of men. It could have been different but it wasn’t. So I wanted to tell the story from the perspective of a man who had insider information regarding management decisions about how to deal with various kinds of production issues.

My novel is historically accurate. Many of the people in the novel were real people. I created a fictional character named Orville Orr, but his buddy McCloud, is a real character. McCloud ran a gambling shanty and sold moonshine to the workers. He was what they called a shack rouster, a deputy sheriff who worked for Union Carbide. What happened in the tunnel and the management decisions that were made are portrayed in the novel in such a way that I hope, along with Orville, the reader will at some point say, “I can’t believe this is going on!” That’s sort of what happens to Orville, but I think it happens to readers as well.

I was surprised to learn that Hawks Nest is categorized as the single biggest U. S. industrial disaster, yet I had never heard of it. Do you think the event is not as well- known because it was an insidious tragedy as opposed to a one-time catastrophic event?

I think that’s part of it and the other part is that Union Carbide covered it up. When Skidmore’s novel came out, a year later you couldn’t buy a copy. The company had it taken off the market. Holmer A. Holt was the governor of West Virginia from 1937 to 1941. His former law firm defended Union Carbide in the suits that were brought against the company and contractor by the workers. Holt took action as governor to remove the Hawks Nest story from the history books. I went through school in West Virginia and didn’t know anything about it. Even today, experienced teachers haven’t heard of the disaster.

So how did you come to know about the Hawks Nest disaster and what inspired you to write a novel about it?

For three years in the latter part of the 1970s, I was the director of a community mental health center in a county next door to Hawks Nest. I began to hear a lot of details about it during those years and the story just stuck with me. It wouldn’t go away. I never intended to write a novel about it. I wrote a short story and in the story there is a man who gets involved with some things that have to do with Hawks Nest. He begins to experience the emotion of what he did at Hawks Nest. I couldn’t stop writing about him. That short story turned into the novel and the character became Orville Orr, the book’s protagonist. What was going on in him was really what was going on in me. I’m deeply troubled by what corporations have done in the Appalachian region in general and in West Virginia in particular.

After writing his expose’ of the Hawks Nest incident, Skidmore died in a mysterious fire and all of his files were removed from Doubleday’s archives. I know that was many years ago, but were you ever concerned about your own safety after you wrote Witness at Hawks Nest?

When the book first came out I made damned sure my doors were locked every night, but I don’t worry too much about it anymore.

One reviewer stated that your book is “a must read for anyone wanting to apply behavior analysis towards improving organizational performance.” How is this story relevant to today’s business and safety community?

Well recently there was an explosion in Middletown, Connecticut, that killed five workers, an accident that didn’t have to happen. On August 28, 2008, there was an explosion at the Bayer CropScience facility near Charleston, West Virginia. Two workers were killed, but there was also a large steel tank that became a projectile in the explosion. When it crossed the plant it crashed within feet of a 40,000-gallon tank of methyl isocyanate or MIC. MIC is the chemical that was released by Union Carbide in Bhopal, India. It immediately killed 3,000 people and in the days afterward probably killed close to 20,000. They make that same chemical at Bayer near Charleston. Hundreds of thousands of people live in the vicinity of that facility. The plant had an explosion and a tank with more MIC in it than was released in Bhopal was narrowly missed. According to the chairman of the Chemical Safety Board following an investigation of the Bayer/Charleston explosion, we came narrowly close to a a disaster that would have dwarfed the disaster in Bhopal.

Several weeks ago, a DuPont facility near Charleston, West Virginia, experienced three chemical leaks within five days. In the last of them, a hose ruptured that was transporting a deadly chemical, phosgene that was used as nerve gas in WWI. It’s still used in chemical production of various kinds, including the manufacture of methyl isocynate. It was being transported through an unsafe hose. The hose ruptured, killed a worker, and released the poisonous chemical into the environment. In smaller ways, these potential disastrous near-misses are an unsettling part of the WV landscape. So I think there is every reason to be very concerned.

Do you think that most companies are really diligent about safety?

Any company that produces chemical byproducts or chemical companies themselves are so complex that the EPA is barely able to keep up with it and they do police themselves, but are quick to cover up, even lie about, incidents and problems. When the Bayer CropScience explosion occurred, they lied about the release of MIC. The Chemical Safety Board documented that there was MIC released; Bayer initially said there was not. They said there was no danger to the community; there was. Government investigators established that there were hazards, there were risks, chemicals were released and the company had systematically lied about it. But go onto Bayer CropScience's Web site and look at their values. What they value is “honesty, transparency, openness, and partnership with the community.”

Then what do they do? They lie until they’re caught. When the CEO was caught by congressional investigators he admitted they company had been lying about the explosion. I want people to keep asking really tough questions of the corporations, including questions about practices that relate to what they put on their Web sites, “We believe in this and this and this,” but in fact, do they really practice what they say they believe? My guess is a few of them do; most of them don’t.

Did your extensive experience with behavioral safety inspire you to write this novel?

Absolutely. I’m passionate about safety. I just can’t tolerate loss of life, loss of limb, or injuries that didn’t have to happen. A company asks for the trust of the worker and at Hawks Nest, for example, they got that trust and they still get that trust today. But people put their trust in a corporation and too often a corporation does not return that trust. They talk about it, but when push comes to shove, and they have to put something on the bottom line, trust goes by the board and they do what has to be done. A corporation has no conscience. They say they do and they talk about values and creating a value-laden environment, but they don’t. Ultimately, it’s a financial operation and it has to be carefully watched.

What types of decisions were made that caused so many deaths by silicosis at Hawks Nest?

The novel includes the true details of when the Director of the WV Department of Mines came to visit and inspect the work at Hawks Nest tunnel. After that he wrote a memorandum directing the chief engineer to supply respirators for the men in the tunnel. After all, every time anybody from Union Carbide, or outside officials, went into the tunnel, they wore respirators, but the workers had none. But the company ignored the memo and never provided workers with respirators.

Could their actions have been due to ignorance? For example, the dust in the mines caused by dry drilling prevented vision beyond a few feet, but did people even know about wet drilling at the time?

Yes they did. In fact dry drilling had been outlawed in England and in South Africa in 1912.

Were they aware of the dangers of silicosis, the degenerative lung disease caused by silica inhalation?

Silicosis s the oldest known industrial disease. It goes back 2000 or more years. It’s been in the medical literature literally for thousands of years. There is no surprise there. It typically takes a longer time of onset. Usually if you work in a foundry or other environment where there is silica dust in the air, it typically takes a period of years for silicosis to develop. But the dust at Hawks Nest tunnel was so intense that men began to drop dead, become ill, and then die, within months. My suspicion is that the company knew about the slow onset of silicosis, figured they could drill the tunnel in less than two years, the men would be gone, and if and when the workers got silicosis they’d be long gone, vanished. What they didn’t count on was the intensity of dust and how quickly it would affect workers.

You gave me a lot of recent examples of near or actual disasters. Do you think a lot of those incidents can be attributed to management decision making?

Absolutely. It starts at the top and it’s easy to blame the victim. The guy is standing by a hose and the hose ruptures; it’s easy to blame him. Maybe he didn’t move the hose properly; perhaps the truth is they’ve cut the budget on maintenance and the hose has ruptured because it was not properly maintained or replaced. That particular facility 20 years ago had 5,000 people working there. Today there are 400 and they haven’t maintained their infrastructure. That’s true all over America.

In your opinion, is management decision making just as or even more relevant to safety than individual worker behavior?

Well I’ve learned a lot in recent years about the whole safety process. There are really two kinds of safety. There’s the BBS performance-based safety we’re familiar with, but another form of safety management is process safety. Process safety is really run by engineers. It has to do with couplings, and fittings, and pressure, temperature and all kinds of complex measurement that goes on to make sure that systems are running the way they need to be running. Typically when you have explosions or large chemical leaks, it’s not a performance problem, it’s a process problem.

But then one takes a step back and thinks, Wait a minute. Who runs the process? How does that happen? That’s the blind spot, the difficult part to penetrate. If process safety is run by engineers, they use an engineering approach, an engineering mentality. They don’t apply behavioral principles to their own behavior by monitoring people who are monitoring the systems. That’s a huge gaping hole in safety and it’s very frightening.

What is the takeaway that you want people to have after they read your novel?

You don’t have to go to India. Go up to the Kanawha Valley in West Virginia. Go up to the Ohio Valley. Eramet Marietta, Inc. has been polluting the Ohio Valley with manganese; the DuPont Washington Works manufacturing facility in Parkersburg, WV, makes the chemical compound that goes into Teflon and Gortex. It’s a carcinogen that induces cancer and it’s widespread throughout the Ohio Valley. DuPont had to pay a fine of $108 million and that’s just the first step. They still have an ongoing investigation about the manufacture of perfluorocarbons.

Part of it is the inadequacy of our research, that there are latent effects that are cumulative and we’re finding that out as we get into years of production and years of pollution. We’ve become so dependent upon chemical industry for our way of life, and part of that dependence has been an acceptance, a too easy acceptance, of the consequences of what they do.

That said, the dark side takeaway is that all too often corporations lie; politicians are in bed with them and they lie too. Workers pay the price. Where is that happening today?In my back yard? Those are the questions that people ought to walk away with.

Excerpt from Witness at Hawks Nest:

“Trouble? What kind of trouble?”

“Well, I know this much. Ninety-nine percent of the time there’s no water coming through those drills. I got to admit, dry drilling is faster than wet drilling; water gums up the drills. But dry drilling puts a powerful amount of dust in the air. And the ventilation’s bad in those shafts. Small fans. Half the time they don’t work. Some days workers can’t see more than ten feet ahead of them.” Holbert stopped speaking as Armen took their plates. After she walked to the kitchen he said, “Men are going to die, Orville. That tunnel dust will kill them. May already be happening.”

“I wonder . . . well, maybe they are turning on the water in the drills. Fans too.”

“One driller told me they do—but only when the state inspectors come around. And that’s not very often.”

Orvilled recalled the afternoon on his first day on the job when he and Bullhead had visited shaft one; the state inspectors and O.M. Jones. Cletus had been riled because of the wet drilling; they wouldn’t make their twenty-two feet. The morning of that same day during their visit to shaft two, its air had been full of dust. Like night and day.

In a completely avoidable disaster, at least 764 men subsequently died agonizing deaths of the lung disease, silicosis. Some accounts report that as many as 1200 perished, but the number is difficult to ascertain since the company secreted the men’s corpses in remote and remorseless graves. Now recorded as the worst industrial disaster in U. S. history, this inhumane event was successfully hidden from the American public by both big business and government entities. This is the story told by Harshbarger in his novel Witness at Hawks Nest. Based on true, horrific, yet historically accurate events, the novel exposes the results that can unfold from behaviors driven by callousness, irresponsibility, and profit-focused greed.

In a completely avoidable disaster, at least 764 men subsequently died agonizing deaths of the lung disease, silicosis. Some accounts report that as many as 1200 perished, but the number is difficult to ascertain since the company secreted the men’s corpses in remote and remorseless graves. Now recorded as the worst industrial disaster in U. S. history, this inhumane event was successfully hidden from the American public by both big business and government entities. This is the story told by Harshbarger in his novel Witness at Hawks Nest. Based on true, horrific, yet historically accurate events, the novel exposes the results that can unfold from behaviors driven by callousness, irresponsibility, and profit-focused greed. Skidmore’s novel is an account from the point of view of three men who are working inside the tunnel and what happens to those men when they find themselves becoming short of breath and unable to do the things they like to do. My perspective is more one of how decisions were made, decisions that ended up killing hundreds and hundreds of men. It could have been different but it wasn’t. So I wanted to tell the story from the perspective of a man who had insider information regarding management decisions about how to deal with various kinds of production issues.

Skidmore’s novel is an account from the point of view of three men who are working inside the tunnel and what happens to those men when they find themselves becoming short of breath and unable to do the things they like to do. My perspective is more one of how decisions were made, decisions that ended up killing hundreds and hundreds of men. It could have been different but it wasn’t. So I wanted to tell the story from the perspective of a man who had insider information regarding management decisions about how to deal with various kinds of production issues. Well recently there was an explosion in Middletown, Connecticut, that killed five workers, an accident that didn’t have to happen. On August 28, 2008, there was an explosion at the Bayer CropScience facility near Charleston, West Virginia. Two workers were killed, but there was also a large steel tank that became a projectile in the explosion. When it crossed the plant it crashed within feet of a 40,000-gallon tank of methyl isocyanate or MIC. MIC is the chemical that was released by Union Carbide in Bhopal, India. It immediately killed 3,000 people and in the days afterward probably killed close to 20,000. They make that same chemical at Bayer near Charleston. Hundreds of thousands of people live in the vicinity of that facility. The plant had an explosion and a tank with more MIC in it than was released in Bhopal was narrowly missed. According to the chairman of the Chemical Safety Board following an investigation of the Bayer/Charleston explosion, we came narrowly close to a a disaster that would have dwarfed the disaster in Bhopal.

Well recently there was an explosion in Middletown, Connecticut, that killed five workers, an accident that didn’t have to happen. On August 28, 2008, there was an explosion at the Bayer CropScience facility near Charleston, West Virginia. Two workers were killed, but there was also a large steel tank that became a projectile in the explosion. When it crossed the plant it crashed within feet of a 40,000-gallon tank of methyl isocyanate or MIC. MIC is the chemical that was released by Union Carbide in Bhopal, India. It immediately killed 3,000 people and in the days afterward probably killed close to 20,000. They make that same chemical at Bayer near Charleston. Hundreds of thousands of people live in the vicinity of that facility. The plant had an explosion and a tank with more MIC in it than was released in Bhopal was narrowly missed. According to the chairman of the Chemical Safety Board following an investigation of the Bayer/Charleston explosion, we came narrowly close to a a disaster that would have dwarfed the disaster in Bhopal. Absolutely. I’m passionate about safety. I just can’t tolerate loss of life, loss of limb, or injuries that didn’t have to happen. A company asks for the trust of the worker and at Hawks Nest, for example, they got that trust and they still get that trust today. But people put their trust in a corporation and too often a corporation does not return that trust. They talk about it, but when push comes to shove, and they have to put something on the bottom line, trust goes by the board and they do what has to be done. A corporation has no conscience. They say they do and they talk about values and creating a value-laden environment, but they don’t. Ultimately, it’s a financial operation and it has to be carefully watched.

Absolutely. I’m passionate about safety. I just can’t tolerate loss of life, loss of limb, or injuries that didn’t have to happen. A company asks for the trust of the worker and at Hawks Nest, for example, they got that trust and they still get that trust today. But people put their trust in a corporation and too often a corporation does not return that trust. They talk about it, but when push comes to shove, and they have to put something on the bottom line, trust goes by the board and they do what has to be done. A corporation has no conscience. They say they do and they talk about values and creating a value-laden environment, but they don’t. Ultimately, it’s a financial operation and it has to be carefully watched.