What Scientists Can Learn from the Science of Behavior

As our Web site shows, ADI serves a range of enterprises that extends across four continents. Amid this diversity, one of our unique strengths applies behavior analysis to managing the performance of scientists in environments like national laboratories and academic centers. Such environments are, indeed, singular places. Scientists, and similarly-employed engineers, expand the boundaries of knowledge in every field that ultimately affects society’s future—from mapping the human genome to exploring the “stuff” of the universe. In an October 18 interview on NPR’s “Wait, Wait, Don’t Tell Me,” Adam Wiess, co-winner of the 2012 Nobel Prize in physics, noted that we have identified only three percent of this “stuff”: “We're really just the frosting on a cake, and we don't know what's inside the cake.”

Moreover, in many ways, individual researchers appear to embody what we call “discretionary effort™,” the accelerated and sustained behavior that generates top performance. Not only do they ground their identity in their careers and adhere to arduous schedules but, far from experiencing the reinforcement of regular success, they also persevere through repeated periods of frustration. At a 1929 press conference, Thomas Edison remarked that “none of my inventions came by accident. I see a worthwhile need to be met, and I make trial after trial until it comes. What it boils down to is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration.”

Moreover, in many ways, individual researchers appear to embody what we call “discretionary effort™,” the accelerated and sustained behavior that generates top performance. Not only do they ground their identity in their careers and adhere to arduous schedules but, far from experiencing the reinforcement of regular success, they also persevere through repeated periods of frustration. At a 1929 press conference, Thomas Edison remarked that “none of my inventions came by accident. I see a worthwhile need to be met, and I make trial after trial until it comes. What it boils down to is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration.”

Given such scientists’ high performance as individuals, managing a scientific team poses a special challenge: ironically enough, the very attributes that motivate what appears to be “discretionary effort” at the individual level can hinder sustainable progress at the team level. Stated simply, the science embodied in behavior analysis reflects a basic principle—that regardless of intention, personality, attitude, ambition, or even genius—every contact among individuals is a reciprocal, dynamic interaction that delivers consequences to all parties involved. We influence one another continuously—behavior science reveals how to exert that influence effectively and ethically.

Furthermore, let us acknowledge two crucial corollaries: first, consequences are not the main cause of lasting behavior change—they are the only cause. Second, individuals’ reactions to a particular consequence (whether they experience it as reinforcing or punishing) depends upon their own previous experiences (i.e., their “reinforcement history”); hence, successful managers know their own people.

The upshot of this brief primer is that unless a brilliant scientist/engineer functions in virtual isolation—a situation that runs counter to most organizational models—he or she influences the culture of the whole work group. Therefore, personal characteristics that might not adversely affect “discretionary effort” at the individual level (e.g., total absorption in the problem at hand; discomfort with interpersonal relations, especially with conflict; lack of skill in coaching, reinforcing, or acknowledging the contributions of co-workers; resistance to change; etc.) could undermine organizational performance. We’ve all seen examples of such phenomena when the most talented physicist in a group founders rather dramatically after being promoted to a manager position.

The upshot of this brief primer is that unless a brilliant scientist/engineer functions in virtual isolation—a situation that runs counter to most organizational models—he or she influences the culture of the whole work group. Therefore, personal characteristics that might not adversely affect “discretionary effort” at the individual level (e.g., total absorption in the problem at hand; discomfort with interpersonal relations, especially with conflict; lack of skill in coaching, reinforcing, or acknowledging the contributions of co-workers; resistance to change; etc.) could undermine organizational performance. We’ve all seen examples of such phenomena when the most talented physicist in a group founders rather dramatically after being promoted to a manager position.

So how, then, does ADI approach this conundrum? How do we gain the participation of top-level scientists and engineers whose typical response to any occasion for “HR training” tends to combine skepticism, impatience, and boredom—with perhaps a soupçon of hostility? The answer is to focus our program on behaviors and results that relate specifically to science. In short, our goal is to link the science of behavior to the behavior of scientists—and, in doing so, persuade the participants that “precision leadership®” is wholly consistent with their scientific training, experience, and values. We believe that this approach may even modify individuals’ “discretionary effort,” in ways that reduce stress.

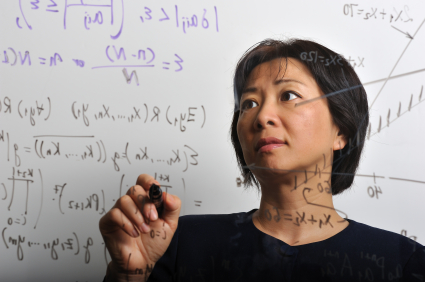

For example, whether the field is physics or behavior analysis, scientists are guided by the “scientific method”—albeit with fits and starts and mistakes and small increments of progress and setbacks and disappointments and revisions, as well as with discoveries and successes. Having verified conclusions and abstracted rules and laws that hold true across diverse contexts, they apply their learning to practical concerns or to further research. But, regardless of the subject matter, the endeavors of any scientific community impact and are impacted by interpersonal behavior, especially verbal behavior—among colleagues, across managerial levels, between project personnel and compliance agencies or funders. Viewed from this perspective, the behavior of scientists reflects the very science that has effectively analyzed that behavior. And, as such, we believe that the insights behavior analysis offers are particularly germane to shaping and sustaining “discretionary effort” that scientific teams experience as both productive and gratifying.

For example, whether the field is physics or behavior analysis, scientists are guided by the “scientific method”—albeit with fits and starts and mistakes and small increments of progress and setbacks and disappointments and revisions, as well as with discoveries and successes. Having verified conclusions and abstracted rules and laws that hold true across diverse contexts, they apply their learning to practical concerns or to further research. But, regardless of the subject matter, the endeavors of any scientific community impact and are impacted by interpersonal behavior, especially verbal behavior—among colleagues, across managerial levels, between project personnel and compliance agencies or funders. Viewed from this perspective, the behavior of scientists reflects the very science that has effectively analyzed that behavior. And, as such, we believe that the insights behavior analysis offers are particularly germane to shaping and sustaining “discretionary effort” that scientific teams experience as both productive and gratifying.