Performance Excellence at Dollar General Distribution Center

Founded in 1939 as J. L. Turner & Son, a wholesale business in Scottsville, Kentucky, Dollar General (NYSE:DG) is a Fortune 500® company and the leader in the dollar store segment, with 8,300 stores in 31 states and $8.58 billion in fiscal 2005 sales.

The company pioneered the dollar store concept in 1955, opening retail stores that sold all items for $1. The format was extremely successful, boosting the company’s sales to $25.8 million by 1965. A few years later in 1968, the company launched its initial public stock offering and changed its name to Dollar General.

Today, Dollar General continues to strengthen its position as a consumer-driven distributor of consumable basics. The company’s mission is simply to serve others. Dollar General carries out this mission by making value and convenience the hallmarks of its business strategy.

- Thirty percent of Dollar General’s merchandise is still priced at $1 or less.

- With small stores averaging 6,800 square feet, Dollar General stores feature a focused assortment of highly consumable merchandise, making shopping for basic necessities simple and hassle-free.

- Dollar General stores are concentrated in under-served rural and urban neighborhoods.

During fiscal year 2005 (ended February 3, 2006) Dollar General opened 734 new stores, including 29 Dollar General markets. These stores are serviced and stocked by eight massive distribution centers (DCs), with a ninth on the way. These DCs, more specifically, the people who work in the DCs and how they have taken ownership of operations, are the focus of this case study.

In 1999, Jeff Sims, joined Dollar General as the vice president of logistics. He brought with him a behavior-based methodology that he had learned and applied with extreme success in his previous position with Hills Department stores. Dollar General’s distribution center network needed some help with the changes brought about by rapid growth, problems with continuity of operations, and productivity issues. They had recently received an overall grade of “C+” from corporate. Seven years later, the DC network has excelled using the behavior-based process that Sims introduced with the help of Aubrey Daniels International (ADI). Attendance, accuracy, quality, safety: every function of the DC is guided by this methodology. The network today still receives a “C” from corporate, but this time the “C” is an accolade that stands for Core Competency.

It's What We Do! Distribution Centers Take Action to Excellence

Jeff Sims, acting senior vice president of distribution for Dollar General, began a basic but telling assessment of distribution center (DC) supervisors and managers when he first arrived at the company. A pivotal question in that assessment was “What is your role as a manager/supervisor?” People inevitably replied in one of three ways, giving answers that Sims noted were the same regardless of the manager/supervisor’s education and experience. The three most common answers to the question were as follows:

- “I am here to make decisions (develop strategic plans, set goals) and then tell other people what to do.”

- “Now that I’m in management, I can show others what they are doing wrong.”

- “I hold other people accountable.”

The last answer was the most annoying to Sims because it highlighted the confusion he observes throughout the business world and the fact that universities teach business majors how to read a spreadsheet, but nothing about how to lead men and women. Admittedly, he may have answered the question in the same way when he was earning his doctorate in marketing, distribution, and statistics, but he and the Dollar General DC managers and supervisors have been on a journey that today makes their view of management and their answer to that question one in the same: the role of management is to help others achieve more.

For Sims, this deceptively simple realization began when he was working with Hills Department stores. The model he used there eventually became the starting template for managing performance in a total of eight Dollar General DCs (with a ninth in progress) for the past seven years. These eight DCs are responsible for the accurate and timely delivery of quality product to 8,300 stores in 31 states.

The Business Challenge

All distribution centers face similar challenges: attendance, accuracy of inventory procedures, time for unloading of inbound merchandise, timely and accurate delivery of undamaged products, safety, cleanliness, cost containment, and overall productivity. When Sims was working with Hills Department stores, the DC network was ineffective, inaccurate, costly, and the sanitation was terrible. Correcting the situation was Sims’ challenge, and one he really didn’t have any idea how to tackle−that is until he attended a conference and listened to the keynote speaker, Aubrey C. Daniels, Founder and Chairman of Aubrey Daniels International (ADI). Daniels spoke in detail about a management process that focuses on the key component of every performance—behavior.

Listening to Daniels brought about a change in mindset for Sims. “How can managers expect people to perform at 100+ percent every day, often under punishing circumstances?” he wondered. It occurred to Sims that every management demand—work faster, pay attention to detail, operate safely, clean up—requires more effort from employees. In all of his years in business, the primary mode of managing performance that he had witnessed was telling people what to do and then punishing them if they didn’t do it. Sims decided to learn more about the behavior-based methods that Daniels had spoken about at the conference. He enrolled in and completed advanced training in the behavior-based methods at ADI’s Atlanta offices. Next, after every manager and supervisor at the DC facility completed the same training, they targeted several specific behaviors for improvement using the new process. Within a year, scores on all behaviors related to absenteeism, time to unload on the inbound, sanitation, accuracy, productivity, and safety had risen from a baseline of 50 percent to 95+ percent. The results were so tremendous that the CEO of Hills asked Sims to come to Boston for a meeting. Upon Sims’ arrival at the office, the CEO shut the door and asked, “What’s going on?” Operating costs had dropped, absenteeism had plummeted, and one could eat off the DC floors. Sims’ answer to the CEO was “Performance Management.”

Diagnosis of Dollar General's Distribution Centers

When Sims was offered a position with Dollar General, he was determined to try Performance Management (PM) in the distribution centers there. Dollar General’s niche was that of a customer-driven distributor of consumable basics, serving low and fixed-income customers, while offering value and convenience. In 1999 the growing company faced several management challenges:

- The company was expanding rapidly at the rate of 600+ stores a year.

- The growth precipitated a pressing need for new DCs to service these stores (one DC built in 1999, another in 2000, and a third in 2001) and to hire, train, and retain employees to staff both new and existing centers.

- The DCs were receiving a “C+” in overall performance from corporate.

- Silo management was alive and well in the supply chain.

- Management focused solely on expense control.

When Dollar General opens a new DC, each with an employee base of 500 or more, the DC employees usually have only 8-10 weeks to become competent at regularly and accurately servicing 600-700 retail stores. These circumstances often create problems with high stress, turnover, and accuracy (meaning the right product in the right place at the right time). These issues, in turn, may impact cleanliness and safety as people rush to meet picking (of products) and shipping deadlines. When Sims came into the picture, Dollar General ran five DCs, which were already operating at levels far above those of the DC chain that he had previously managed. However, although the facilities were staffed by good managers and employees, room for improvement existed.

To begin, Sims called all of the DC managers together and told them about his plans to apply behavior-based Performance Management as the way of management at the distribution centers. At least one veteran who had successfully run DCs for 25 years wanted to know why change was necessary. Sims simply asked for a volunteer to try the process and he got one—the manager of the new state-of-the-art, million-square-foot Southeast DC, Bob Barnes.

Assessing Operational Needs

At this point, Wes Spring, a behavioral consultant with ADI, joined Sims and Barnes at the Florida facility. Employees and managers were surveyed and interviewed in detail regarding the specifics of job tasks and operations. During this interview process, Sims once again heard the three common answers to his role-of-management question. Spring and other ADI staff carefully observed workers on the floor and asked the workers questions about how they completed required duties.

Barnes and his management team quickly discovered that two ways are available for approaching standard operating procedures (SOPs). Management could either sit at headquarters talking about how they thought employees should, for example, pick products for shipment or they could go out and actually talk to the men and women, explain productivity goals, discuss the safety issues involved, and then ask for their advice. He soon understood that employees are going to figure out the best and most expedient way to get their jobs done.

Interviewing, observing, and studying existing data, management and ADI staff assessed every single function inside the building. Importantly, not only did they discuss actual work content, but they asked employees about how the requirements of the work and desired results were communicated. They also asked employees about their expectations of managers and supervisors. This interviewing process provided some eye-opening observations about management behavior and highlighted the best practices of those employees who consistently excelled. Observations and discussions about the job were integral to the improvement process, according to Spring. Instead of a group of managers or executives determining what employees should be doing, the people who actually did the work were revealing the best ways to do the job as well as the barriers and hindrances to performing their jobs optimally. Spring and his associates also studied and analyzed the existing operations data to determine intervention needs.

The behavioral performance analysis performed by ADI professionals identified the unique issues of culture, systems, processes, and structures that supported or impeded performance. The analysis also refined the expectations for Return on Investment (ROI) of a Performance Management system implementation from an employee, customer, and financial perspective. Exemplary performers (those producing results the right way) were selected as standards of measure. ADI also identified aspects of the business culture, work systems, processes, and skills that might be keeping others from demonstrating the same characteristics as best-practice performers. The following criteria were applied to all components of the data analysis and assessment:

- Direction and alignment—the clarity of business direction and the alignment of drivers, systems, results, and behavior across the organization; the use of pinpointing technology (defined as performance expectations stated in terms that are measurable, observable, reliable, active, and under the performer’s control) as used when communicating strategic and tactical results, value-added and critical behaviors and consistency in how systems support performance requirements

- Implementation—how strategies and executions of strategies occur, the assignment of roles, allocation of resources, communication (including information regarding change initiatives)

- Consequence Management—existing processes in place for influencing the direction of behavior

- Measurement—examination of systems for obtaining performance data about results and behavior and the use of performance feedback

- Organizational effectiveness—the extent to which systems complement each other to provide maximum value with little or no redundancy

The needs assessment uncovered both positives and negatives in current procedures, but the standout discovery was inconsistency of operations between individuals with the same jobs and also with the management of every DC. Consistency of operations bolstered by the discovery and installation of best practices became an umbrella goal for Dollar General. Also, by asking for the input of the employees, the PM team had already started the workforce on the first steps of positive ownership of their jobs and their company’s future.

Design of the Performance Management Model

Since 1939 Dollar General has operated with the mission of “A better life for everyone.” This commitment to employees as well as customers fits well with the mission of Performance Management—to shape and optimize performance through the systematic use of primarily positive consequences. The techniques and practices of Performance Management are derived from the field of behavior analysis, or the scientific study of behavior. Applied behavior analysis refers to the practice of applying research findings to the workings of the real world. Performance Management, as developed by Aubrey C. Daniels, Ph.D., is a branch of applied behavior analysis that focuses on the workplace. Basic behavioral research has been conducted in this area for over a century (Thorndike, 1898; Watson, 1913; Skinner, 1936) with applied research beginning in the 1950s. However, business and industrial applications began in the 1960s.

At first glance Performance Management may seem simplistic, but in practice, each step of the process must be specific and systematic to be continually effective. Daniels, the founder of PM, describes it as “A way of getting people to do what you want them to do and to like doing it.” Sims boils his definition down to “planning and providing the right types of consequences for the behaviors that you want more of or for the behaviors that you want less of.” He notes that a supervisor can’t walk out to a group of 800 people, say “I want you to be more productive” and then walk back into his office and think, “Boy what a great leader I am.” Amazingly, this is the way most management works . . . or doesn’t work. Directives, signs, training, instructions, demands: in PM terms these are all antecedents to behavior. Though part of the behavioral chain, antecedents only affect behavior if connected to a consequence that is likely to occur, whether that consequence is positive or negative.

While four types of consequences (positive reinforcement (R+), negative reinforcement (R-), punishment (P+), and penalty (P-)) shape and determine all behavior, Performance Management focuses on positive reinforcement as the only consequence that optimizes performance.

Strangely enough much work behavior is still driven by negative reinforcement because reprimands and threats (overt or implied) provide a deceptively quick solution to performance problems. Negative reinforcement is overused because it provides the person dishing it out with an immediate reaction, therefore positively reinforcing that person for using a consequence that is ineffective, even damaging, over the long term.

Yet negative reinforcement as a primary consequence never drives discretionary effort™—the want-to performance that rises above and beyond the basic requirements of a job. Also, negative reinforcement usually requires the constant vigilance or presence of the threat, meaning that supervisors and managers who manage primarily with negative reinforcement always have to keep an eye on things or little to nothing will get done. This isn’t a good way to run a business or to work for a business. PM focuses on getting the most out of employees by providing them with as many positive consequences for desired behaviors and results as possible. These consequences can be woven into the work process or into the systems and environment of an organization; they can be self-fulfilling job activities, and/or they can come in the way of acknowledgment and respect from management. So many positive consequences could be available at work that an entire listing would be impossible.

Many executives and managers, when asked how to change results, reply with platitudes such as

- “We’ve got to get with the program.”

- “We need more commitment.”

- “I want 110 percent effort.”

- “I need people with focus.”

These general statements are useless for accomplishing any real change because employees have no way to commonly interpret the actions that they should take. Anyone who is trained in Performance Management principles readily recognizes such communication as weak antecedents to behavior change.

An important note is that all results are attained by behaviors, so behavior is usually the targeted choice for change. The Southeast DC presented the following reasons that the PM model was the improvement process of choice.

Performance Management: A Methodology Match

- Provides a systematic process

- Focuses on pinpointed behavior/results expectations

- Utilizes positive reinforcement as its primary behavior consequence

- Focuses on behavior measurements and result validation

- Utilizes a behavioral approach to problem solving

- Reinforces desired behaviors and celebrates result improvement

Implementing Performance Management

ADI’s Wes Spring first trained every manager and supervisor of both shifts at the Southeast DC. The training itself was designed and implemented on PM foundations. During training, attendees received social recognition, feedback, and occasionally, tangible items as they progressed through the sessions. After the training, Spring and the ADI consultants followed up for several weeks, scheduling meetings with each person, and providing feedback and support in activating their improvement plans.

The implementation of Performance Management is 100 percent open book. All employees are informed of its methods and participate in identifying the key behaviors that determine critical results. At the Southeast facility, quality, including timeliness, accuracy, and no damages, was the first area pinpointed for change. Sims remarks that somewhere around the time that people are about to enter high school, they all begin to accept the concept that work shouldn’t be fun. This was a view that management decided to change with the motto of “We strive to make work simple, smart, and fun!” by achieving the following goals:

Implementation Strategy: PM! This is How We Manage!

- Develop a systematic process for achieving results through managing behaviors.

- Change assessment from results to behavior and results.

- Reinforce those who reinforce others.

- Establish a want-to service environment.

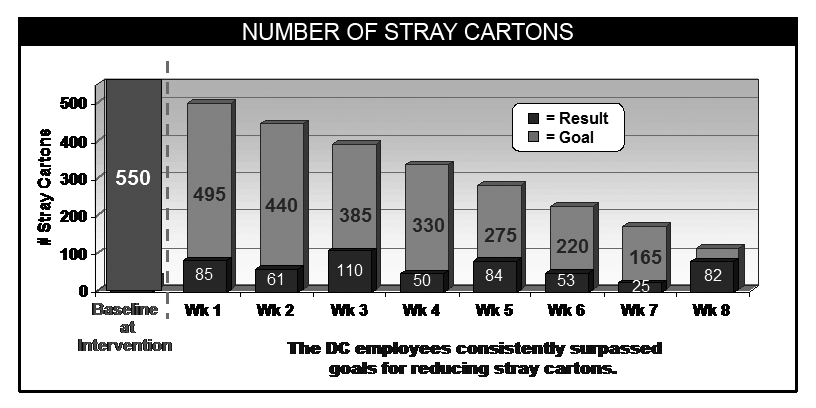

These were not platitudes, because every employee team on the floor set out to pinpoint specific activities and results that reflected the above values. They found that when they pinpointed, observed, measured, and provided constructive feedback and positive consequences for one behavior that other important variables improved as well. For example, a DC is typically 1,200,000 square feet with over 74,000 pallet locations. When a facility is clean, product picking is more accurate and load time is reduced. If inventory is accurate, hundreds of workers spend less time looking for product. Therefore, when one element of operations improves, overall productivity improves as well. This chain effect proved true for other areas of quality, because the better the inventory, the more accurate the orders, and the more satisfied the customer. Many of the behaviors identified could be self-observed and measured and soon the entire workforce was participating in creative ways to meet the next performance criteria.

Areas Addressed

- Attendance

- Damages

- Hourly Throughput

- Load Quality

- On-time Shipping

- Picking Accuracy

- Productivity

- Receiving Accuracy

- Safe Behavior

- Sanitation

- Supervisors Positively Reinforcing

After only 60 days of implementing PM, the

At the

Other groups within the DC put a new spin on the Driving for Success theme with a golf theme. They tallied their checklist of behaviors to earn the right to “putt for prizes” at the close of the business day. These prizes were inexpensive items that added an element of fun to often repetitive work. Group celebrations ranged from small gatherings, during which accomplished milestones were announced, to the opening of vending machines, but the social interaction, involvement, and management interest and acknowledgment fueled the process. The Midwest DC sped past other facilities that had been in operation for years, all by identifying 10 key behaviors that enabled them to maximize inventory accuracy, quality, and overall productivity.

Performance Management methods were subsequently implemented in a total of eight Dollar General DCs with the ninth to be opened in late 2006. The new facility will employ 550 people. Before opening the doors, every manager and supervisor for the facility has already been trained in PM methods. Although the Southeast and then the Midwest DCs were the templates for PM implementation, lessons have been learned and applied as best practices throughout the DC network, thus continually improving the continuity of operations. The Performance Improvement Plan below demonstrates how strategic and specific behavior change can be accomplished with a bit of added fun.

Sample Performance Improvement Plan (PIP)

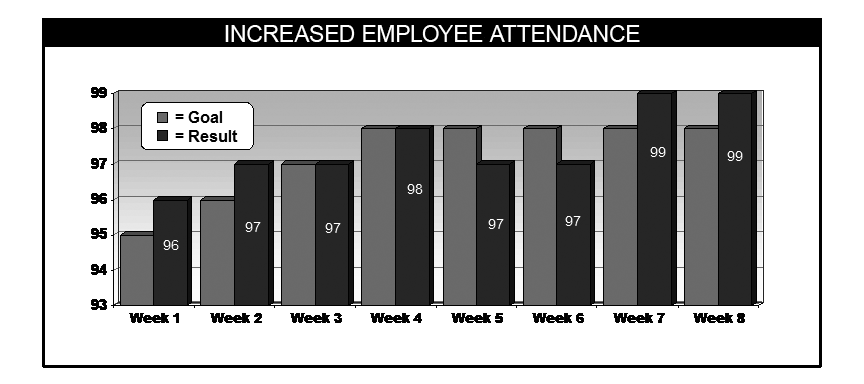

Improving 2nd Shift Employee Attendance

Purpose:

High absenteeism in a distribution center, especially on Sunday evenings, means our stores and customers may not get the products they need. It also means that our fellow employees who are here are trying to do the work of two. The goal of this PIP is to improve 2nd shift employees’ daily attendance.

Where did we start?

Baseline Data:

89% employee attendance on Sunday

94% employee attendance Monday through Thursday

Where did we want to be?

Goal: Maintain 98% Sunday through Thursday

Sub goals:

Week 1 = 95%

Week 2 = 96%

Week 3 = 97%

Week 4 = 98%

Weeks 5-8 = Habit strength – Maintain 98%

What Behaviors Did We Focus On?

The Employee Behaviors:

- Come to work and be in assigned areas at scheduled start time.

- Maintain a steady work-pace up to break time.

- Come back from breaks and lunches on time and be in assigned work areas at start-up from breaks and lunches.

- Maintain a steady work pace up to end of shift.

- Stay here with everyone else and work all of our scheduled hours.

The Supervisor Behaviors:

- Be in work area at scheduled start time to shake hands and issue positive reinforcement (R+) tickets to employees demonstrating desired arrival behavior.

- Observe work paces before break times including lunches and issue positive reinforcement (R+) tickets as desired work paces are observed.

- Be in work area after all breaks and lunch to issue positive reinforcement (R+) tickets as employees demonstrate desired “return” behavior.

- Be in work area at the end of the shift to issue positive reinforcement (R+) tickets to employees who worked until the end of the shift.

- Provide results feedback in departmental start-of-shift meetings.

- Take all employees by the DG store at the end of each week to trade their tickets in for a sundry of items.

- Record on a spreadsheet those employees who demonstrate 100 percent of the behaviors every day for the final drawing.

- Provide ideas and pictures for the visual feedback board on the North Wall.

The Manager Behaviors:

- Reinforce supervisors as observed for demonstrating their desired behaviors.

- Conduct a facility-wide, kick-off meeting with 2nd shift employees and management.

- Walk the building each evening to thank employees for their attendance behaviors.

- Provide results feedback in DC start-of-shift meetings.

- Hold a facility-wide celebration at the end of the PIP if results are realized.

How Did We Do?

How Did We Celebrate?

Week 1: Supervisors in 1950s garb danced into the South Drive Aisle to the Happy Days theme song. The Shift Manager gave an overview of the Performance Improvement Plan and what was in it for the employees. He discussed the positive reinforcement (R+) ticket and the value each ticket held for items.

Week 2: Colorful and fun visual feedback board goes up!

Week 3: Manager thanks employees at exit at end of shift – Store opens and visits to redeem tickets begin

Week 4: Pictures of employees are posted on visual feedback board and the store visits continue

Weeks 5-8: Store visits continue

Final celebration: Invitations to a 1970s Party go out to all employees. They are invited to come to work dressed in 1970s garb – ’70s music will be played and there will be dancing and games at lunch and at breaks.

This facility-wide celebration was held on the last day of the Performance Improvement Plan. We used the theme of ’70s music and each management member chose a favorite ’70s song to come out dancing to, dressed in the appropriate garb.

The Shift Manager (dressed as Austin Powers) then hosted a game show entitled “Who Do You Know?” Members from the audience (employees) were chosen to participate as contestants and play for prizes. The object of the game was to guess which clue described which member of management. We also included a drawing for those employees who got all of their reinforcement tickets every day demonstrating 100 percent of the attendance behaviors.

***

Similar Performance Improvement Plans have successfully helped employees in Dollar General’s DC network achieve behavioral and results goals in every aspect of operations. (See results section.)

Support On The Job

The men and women on our DC floors are doing very difficult work,” stated Sims. “Like everyone, they would like to be recognized, but in the majority of companies that never happens. It’s astounding.” Since on-the-job support and reinforcement is the foundation of PM, it is somewhat difficult to separate the support functions from the process itself. Support in the form of feedback, social and tangible reinforcement, and celebration is imbedded in and drives the ongoing process.

Support and reinforcement is a core part of every Performance Improvement Plan in every facility. It is reflected in recognizing everyday actions. For example, one DC created a special club for one of its toughest jobs—case pack picking. The men and women employed in this capacity move 260 cartons, weighing an average of 18 pounds each, by hand for nine hours per day, for a total of 42,120 pounds per person every day. This is the equivalent of moving 21 tons of product one case at a time. It is difficult physical labor, so the DC added some support for these people who probably have never received recognition in other such jobs. The DC created the 300 Club for anyone who can pick 300 cartons a day for three weeks. Quite a few employees have earned membership which includes special recognition and a shirt with the 300 Club logo. The shirt affords them, not only recognition among peers, but a story to tell about the details of the job that they do. The facilities also offer certifications for best practice employees such as the Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) Craftsman award, for those who master the criteria of several jobs within the facility. One grandmother cried when she received the award, noting it was the first formal recognition she had received for anything since high school. Many younger supervisors come into the facility thinking that they will be seen as soft by some of the DC veterans if they try to recognize them for their efforts but they soon learn that isn’t the case. “No matter how old you are, you will respond to genuine reinforcement,” Sims said.

Ideally, PM would be an ingrained part of every company from the executive suite to the work floor, according to Sims, but the primary reasons that he could foresee any failure of such a process would be lack of active support or shear neglect. Every two weeks Sims sends out a conference call agenda to each DC manager. The priority of the agenda is a different question regarding PM implementation. For example, one week the question may be, “How are you reinforcing your managers for reinforcing their supervisors for using Performance Management?” This is an important question because the hourly personnel aren’t the only employees who require recognition and support for their efforts. During the two-hour conference calls, DC managers share successful Performance Improvement Plans and best practices which can then be implemented in other DCs. Even when the subject moves to general operations, the managers now speak the same language because PM is the management method that drives all other operations. “When our men and women get together to make a change or address a problem, we want them to think PM,” Sims said. “No matter what the problem is, the solution to it is a change in behavior. I would say the same thing if I worked in a bank, a hospital, or a lawn care company.”

Training, of course, is integral to support. All supervisors and managers are trained in Performance Management before their first day on the floor. Also, each DC has a designated Performance Manager who is certified and licensed each year to teach within their DC. “They know that we are going to pinpoint what we want; measure the behaviors we want, provide feedback to the employee, and plan and deliver predominantly positive consequences,” said Sims. One newly hired manager, who had been in management positions for years, stated that in all of the companies he had worked for he had never been trained how to manage people. Training and continual follow-up is a key component of supporting the process, as far as Sims is concerned. “PM eliminates the uncertainty about how you are going to manage and teaches you how to lead women and men,” he said.

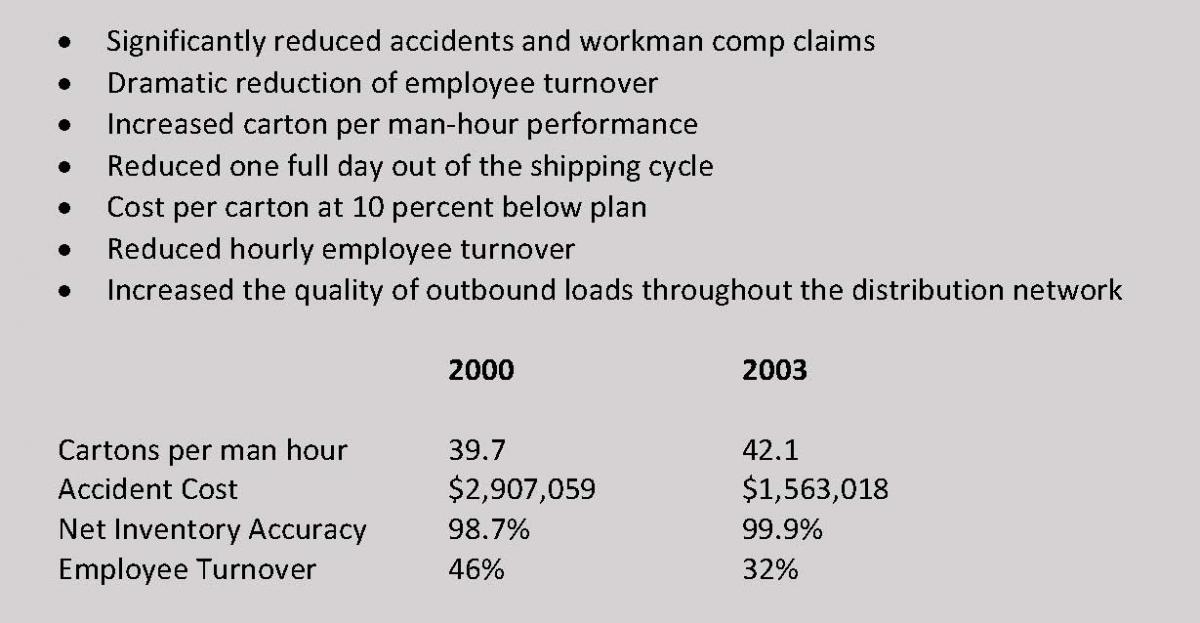

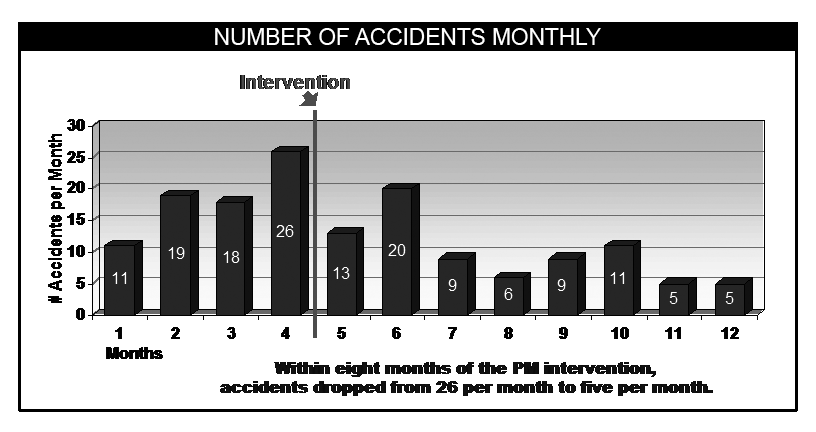

Results That Keep On Coming!

Today, Dollar General cites distribution as one of its core corporate competencies. For seven consecutive years, the DCs have improved performance, including (with the exception of one month), a steady reduction in accidents. The DCs also use PM to address safety, focusing not on hanging up signs, but by reinforcing employees for using safe behaviors. “I know of no other project, plan, or trial in my career that reduces the number and severity of accidents other than Performance Management,” said Sims. “I’ve never seen anything outdo it.”

One of the first lessons learned about attaining results was that you definitely get more of the behaviors you reinforce. When the start-up

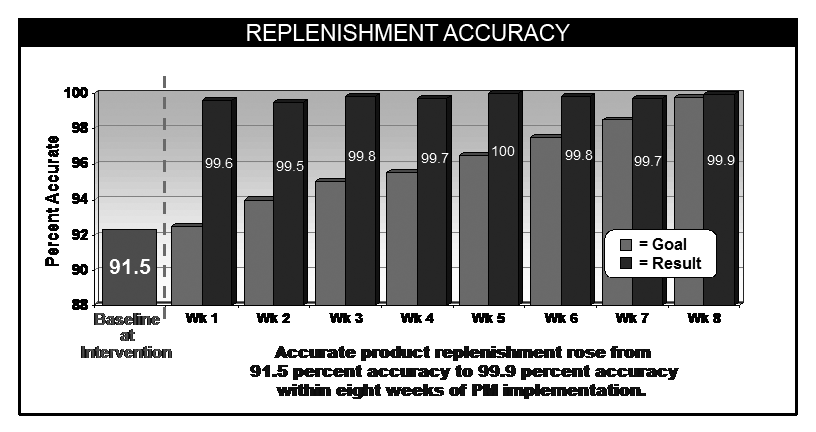

Following are examples of the many results achieved via the Performance Management process at Dollar General’s eight distribution centers over the past seven years:

- Successful start-up of Midwest DC

- DC Network improvement in sanitation

- Above-standard inventory location accuracy in Southeast and Midwest DCs

- Eliminated wall-to-wall, year-end inventory

Exhibit A: Sample Performance Improvement Plan (PIP) & Results

Purpose: Increase freight flow through the DC

How This PIP Will Work:

- Hourly employees will be observed at least once per day to see if they are doing the desired behaviors.

- Each performer will have a behavior card to attach to their ID badge.

- Performers will receive stickers for their behavior card for exhibiting desired behaviors.

- For every five (5) stickers, performers will receive one “Rollin’ with the Flow” PM dollar to be used at the PM store.

(NOTE: Behaviors were delineated for every type of worker in the facility, which are too numerous to list here.)

Shipping Loader

- Leave for and return from breaks and lunch on time.

- Retrieve and return pallet jack to designated area.

- Load merchandise at a pace that ensures standard is met.

- When no freight is coming in your assigned lane, assist the lane on either side of you.

Repack Stocker

- Leave for and return from breaks and lunch on time.

- Have all needed tools, tape, box cutter, and gloves when you go to your assigned zone.

- Check merchandise off the stocker report as you remove it from the pallet.

- Properly cut cases with half-moon shape.

- Make sure back stock is in the correct location and the location is written on the case.

- Make sure all forward pick locations are filled with available back stock.

- Make sure all replenishments are processed before you leave.

Repack Inventory Clerk

- Research and make adjustments to all incorrect forwards.

- Ensure all new product is located in correct zone by profile.

- Research and adjust all incorrect reserve locations.

Security

- Ensure all appointment drivers are checked in no earlier than one hour before their appointment time.

- Release drivers to the receiving dock no sooner than 15 minutes prior to appointment time unless otherwise directed by supervisor.

- Ensure all outbound seal and trailer information is correct on store delivery trailers before they leave the yard.

Celebrations

We will celebrate weekly, based on cartons per man hour (CPMH) from Inbound and Outbound sub-goals.

Results

We reduced cartons per man hour from 43.6 in November to 42.1 in January.

Exhibit B: Sample Performance Improvement Plan (PIP) & Results

Purpose:

Improving the employee morale and attendance

PIP Theme:

“Your Attendance Shines Through”

Primary Performers:

2nd Shift Inbound Manager & Supervisors

Attendance Baseline:

84% Weekly Attendance Level

Attendance Results:

92% Weekly Attendance Level

Desired Behaviors:

Manager:

- Model and coach reinforcement behaviors with supervisors

- Establish attendance baseline and measure daily/weekly

- Establish attendance as a focal point in daily meetings

- Daily attendance-related positive reinforcement for supervisors and employees

- Celebration follow-up to ensure timely consequences

Supervisor:

- Reinforce each employee for daily presence at work

- Discuss benefits of good attendance during daily meetings

- Reinforce employees who have perfect attendance during daily meetings

- Update graphs on a daily basis and provide visual feedback

- Provide personal feedback for attendance behavior

Employees:

- Report to work on time for beginning of shift

- Report to work area on time following each break period

- Stay at work for the entire shift

Consequences:

- Immediate social recognition at daily meetings

- Celebration for achieving 1st Sub Goal – Free milkshake coupon from Sonic

- Celebration for achieving 2nd Sub Goal – Soda & candy bar break

- Celebration for achieving Final Goal – Hamburger, hot dog cookout

- Intermittent celebrations executed numerous times in subsequent months

Summary of PIP:

The 2nd Shift Inbound team attendance baseline of 84% was moved to a level that averages 92% or higher on a weekly basis. Months after the formal end of the PIP, habit strength is easily validated through observation of supervisor and manager behavior during start-up meetings, continuous feedback through visual aides, as well as by consistent attendance levels demonstrated by the employees. Celebrations are now planned on an intermittent schedule, providing our management team more freedom to be creative and spontaneous with the celebrations.

This PIP is one of my personal favorites because it changed attendance-related behavior at both the exempt and non-exempt levels, positively impacting our entire 2nd shift team. Equally, if not more impressive, is the fact that desired behavior and results continue months after the PIP officially ended, with attendance levels averaging +92% since September 2005. This specific PIP is one of our best examples of how pinpointing desired management behavior can influence the team’s (employees’) behavior.

Exhibit C: Sample Performance Improvement Plan (PIP) & Results

Purpose: Decrease Zero Picks

One of our more successful and possibly entertaining PIPs was titled “Ante Up.” This PIP was created to help decrease our zero picks. A zero pick is when our on-hand inventory shows that we have zero cases in an order-filling forward location, when, in reality, there are cases in the forward location. This error has many causes but all point back to inventory discrepancies. After picking these cases, our system will alert us that we have “picked against zero (PAZ).” This seriously affects our inventory accuracy in our order-filling pick locations.

With each PIP is a baseline, sub-goals and a final goal. The baseline is information gathered before the kick-off of the PIP. In our case we had 121 pages per week on our reports of “PAZ.” Our goal was to reduce the amount of pages by 50 percent within a six-week period. The performers for this PIP were our supervisors. Each department that participated in the PIP was given a list of behaviors that were to be accomplished on a daily basis. These behaviors were developed by doing an analysis of how each area influenced the results.

Below are some of the behaviors that were developed after performing the analysis:

- Supervisors will run a pick line report for mod/zone, and verify inventory is correct. Report discrepancies to Inventory Control.

- Supervisors - Print PAZ report after each batch and reinforce or give constructive feedback to employees immediately after research is complete.

- Supervisors - Run transaction history four times daily (two times per supervisor) and spot-check staged pallets for accuracy.

- Supervisors will clear the item validation report four times daily.

- Supervisors will ensure the RTS process is completed for each bust out under 0 cases and verify the yard for Cross dock trailer accuracy.

- Supervisors will ensure the paperwork for RTS items is delivered to Inventory Control.

- Walk/Ride area daily to observe and socially reinforce

- Designated supervisor on each shift will run the PAZ report each day.

- Post daily results in area and celebrate improvements with the team daily and weekly.

- Update graphs/visuals in chat room daily and weekly.

If all the listed behaviors were completed for the week the supervisors were given cards, and we played various card games in our morning supervisor meetings. The player with the best hand was given a small but meaningful tangible prize.

Below are the sub-goals and celebrations associated with those sub-goals:

Sub-goal #1: 76-90 pages

Managers positively reinforce supervisors in morning start-up meeting

Sub-goal #2: 61-75 pages

Managers send Operations and DC Manager an e-mail on Supervisors’ contributions and talks with Supervisors one-on-one

Sub-goal #3: 51-60 pages

Managers buy supervisors lunch on following week & positively reinforce

Sub-goal #4: 50 or fewer pages

Manager gives supervisors a shortened work day or selection of any items listed above

Exhibit D: Additional Results Graphs

On the first week of the PIP we saw immediate improvements. We averaged 63 pages per week over a six-week period. We continue to reinforce the behaviors developed during the PIP and the results show that we are now averaging 54 pages per week; this is an average of 5 pages per shift. This information has been accumulated since February 2006 until March 29, 2006.

Conclusion

The Dollar General DC network documented a return on investment (ROI) within the first year of implementing the Performance Management process. Each DC spends the equivalent of one-fifth of its total labor costs for training and implementation of Performance Management. “This process pays for itself,” said Sims. “When we teach people how to manage that kind of labor investment, we get a payoff in less than six months.”

Other payoffs include a culture change in the DC network—one of open dialogue, clear expectations, honesty, and mutual respect between management and employees. The consistency of operations has been achieved and, due to ongoing networking between DCs, is consistently refined. Sharing of best practices now means more recognition for individuals and groups. Work teams and individuals self-measure using observable behaviors and results and managers and supervisors measure their own key behaviors on a daily basis. Employees throughout the DCs continue to create and take ownership of improvement plans that make work fast, smart, and fun. Sims concludes, “The major change is that this is the way we manage throughout the network and the point is that with this process, you can positively influence anything.”

* * *