Ability is not an Inside Job

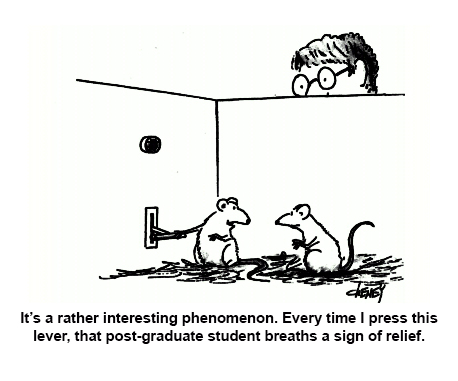

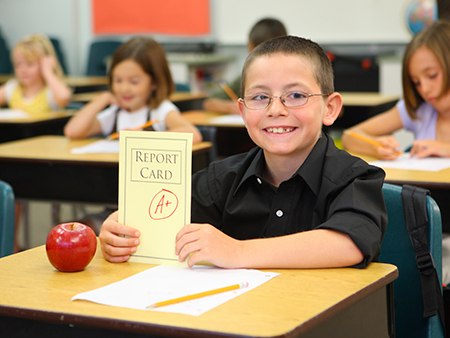

On a recent exam, one of my students observed that her rat had the ability to get the reinforcer.” Relatedly, star athletes often are said to have “great athletic ability,” scholars are said to possess similar “intellectual abilities,” and novelists often are singled out for having “the ability to write.” When you think about it, references to abilities, whether they involve getting food, earning good grades, or understanding something are very common in our ordinary language.

On a recent exam, one of my students observed that her rat had the ability to get the reinforcer.” Relatedly, star athletes often are said to have “great athletic ability,” scholars are said to possess similar “intellectual abilities,” and novelists often are singled out for having “the ability to write.” When you think about it, references to abilities, whether they involve getting food, earning good grades, or understanding something are very common in our ordinary language.

But what does it mean to possess or have an ability? Sometimes an ability is just a description of circumstance, another way of saying that a person has a particular history that enables certain kinds of behavior. When used in this way, ability becomes a shorthand description of actual behavior, past or present. A published novelist obviously can, by society’s standards, write at least sufficiently well that someone is willing to publish her work. When my students talk about the rat being able to get the reinforcer, they (hopefully) are merely describing the fact that the rat (a) has learned where the reinforcer can be accessed and (b) the response necessary to get it. In this context, saying that someone has the ability to do something is tantamount to saying they have the necessary history and experience for doing something.

But what does it mean to possess or have an ability? Sometimes an ability is just a description of circumstance, another way of saying that a person has a particular history that enables certain kinds of behavior. When used in this way, ability becomes a shorthand description of actual behavior, past or present. A published novelist obviously can, by society’s standards, write at least sufficiently well that someone is willing to publish her work. When my students talk about the rat being able to get the reinforcer, they (hopefully) are merely describing the fact that the rat (a) has learned where the reinforcer can be accessed and (b) the response necessary to get it. In this context, saying that someone has the ability to do something is tantamount to saying they have the necessary history and experience for doing something.

Interjecting the word “ability” into the equation muddies the water, for too often the ability to do or achieve something becomes the cause of the very behavior from which it derived. And then it mysteriously becomes the  cause of the cause of that behavior. Athletes perform well and novelists write because they have the ability to do so. The operative word here is because. As with many other so-called psychological traits, ability starts with a behavioral observation, then is made real (becomes reified in the language of philosophers and psychologists), that is it becomes more than just a shorthand for a behavioral description. It becomes an entity, a thing. It is something people possess, that they have. Thus, what began as a simple behavioral observation morphs into something that must exist. If it exists, it must exist somewhere. And where might that somewhere be? Some nebulous place in the brain or mind. At this point ability becomes an inside job. It isn’t too long before the ability not only exists, but because it exists it must have a reason for existing and that reason is to … cause behavior. Athletes and novelists perform as they do because of their abilities. How completely circular is that? The ability that began humbly enough as a shorthand description of behavior not only morphs into an entity, but a causal one at that.

cause of the cause of that behavior. Athletes perform well and novelists write because they have the ability to do so. The operative word here is because. As with many other so-called psychological traits, ability starts with a behavioral observation, then is made real (becomes reified in the language of philosophers and psychologists), that is it becomes more than just a shorthand for a behavioral description. It becomes an entity, a thing. It is something people possess, that they have. Thus, what began as a simple behavioral observation morphs into something that must exist. If it exists, it must exist somewhere. And where might that somewhere be? Some nebulous place in the brain or mind. At this point ability becomes an inside job. It isn’t too long before the ability not only exists, but because it exists it must have a reason for existing and that reason is to … cause behavior. Athletes and novelists perform as they do because of their abilities. How completely circular is that? The ability that began humbly enough as a shorthand description of behavior not only morphs into an entity, but a causal one at that.

Abilities don’t cause anything. They are not inside jobs, things living inside us or in the nether world of mentalism waiting for the chance to cause us to do breathtaking things. They are as often as not simply the behavior we observe or, if not that, a shorthand for a unique history that makes certain other behavior more likely. The next time you are tempted to talk about your own or another person’s ability to do this or that, self-edit. Change that nebulous inside concept to an outie – an action – by talking about what the person is doing now or about their history of certain kinds of interactions with their environments, rather than their “abilities.” We might say instead, “Her history of practice helped to develop her excellent skill in piano playing…or writing…or in resolving conflicts.” Not doing so perpetuates an unfortunate myth about the determinants of our behavior.

Abilities don’t cause anything. They are not inside jobs, things living inside us or in the nether world of mentalism waiting for the chance to cause us to do breathtaking things. They are as often as not simply the behavior we observe or, if not that, a shorthand for a unique history that makes certain other behavior more likely. The next time you are tempted to talk about your own or another person’s ability to do this or that, self-edit. Change that nebulous inside concept to an outie – an action – by talking about what the person is doing now or about their history of certain kinds of interactions with their environments, rather than their “abilities.” We might say instead, “Her history of practice helped to develop her excellent skill in piano playing…or writing…or in resolving conflicts.” Not doing so perpetuates an unfortunate myth about the determinants of our behavior.