Being Objective about Objectivity

Everyone concerned with evaluating human behavior is concerned with objectivity. Jurors are screened to ensure that they do not have preconceived opinions about a defendant’s guilt or innocence. Teachers aren’t usually allowed to have their own children in their classrooms. Psychologists consider it unethical to treat close family members, and in many work situations there are safeguards to prevent husbands and wives being in direct supervisor-supervisee relationships.

Everyone concerned with evaluating human behavior is concerned with objectivity. Jurors are screened to ensure that they do not have preconceived opinions about a defendant’s guilt or innocence. Teachers aren’t usually allowed to have their own children in their classrooms. Psychologists consider it unethical to treat close family members, and in many work situations there are safeguards to prevent husbands and wives being in direct supervisor-supervisee relationships.

Objectivity is both a scientific ideal and a practical tool. It developed out of what we might call a realist view of science, which, in simple terms, assumes that a world exists outside of our experience of it. Science is seen by some as a tool for mapping reality. Biases, which are failures to be objective, distort our view of the world as it really is and therefore are a hindrance to achieving an accurate map of “the way things really are.”

We also can treat objectivity as a more pragmatic issue and finesse any necessity of the realist’s assumption. A pragmatic view of objectivity requires only that objectivity be useful in achieving the behaviorist goals of prediction and control of behavior. From a pragmatic point of view, biases are a hindrance if we are trying to predict and control behavior. A matter of seeing the world through rose-colored glasses, so to speak. Regardless of how objectivity is viewed, it is generally seen by scientists of all types as something we should adhere to in their work.

We also can treat objectivity as a more pragmatic issue and finesse any necessity of the realist’s assumption. A pragmatic view of objectivity requires only that objectivity be useful in achieving the behaviorist goals of prediction and control of behavior. From a pragmatic point of view, biases are a hindrance if we are trying to predict and control behavior. A matter of seeing the world through rose-colored glasses, so to speak. Regardless of how objectivity is viewed, it is generally seen by scientists of all types as something we should adhere to in their work.

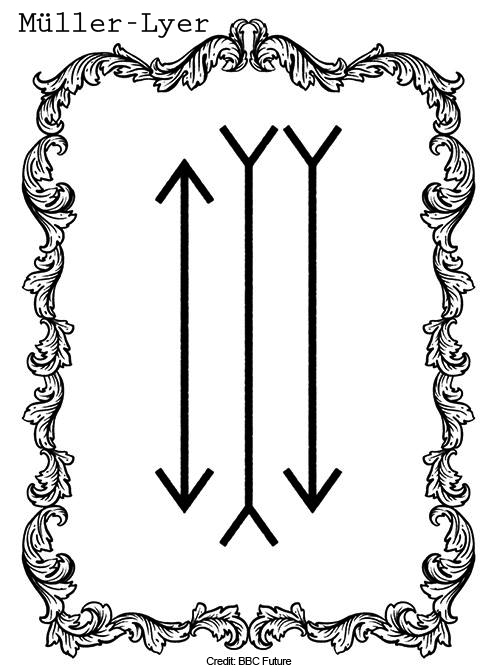

There are limits to objectivity, though. Our physiological equipment imposes some of these limits. For example, some colors and sounds that can be made accessible with certain kinds of instruments are, without those instruments, inaccessible to us humans. We also all come into a situation where objectivity is called for with different histories and expectancies that make us less than perfectly objective. The classic Müller-Lyer optical illusion, shown here, illustrates in a very simple way how context affects our ability to judge something objectively even simple things like the length of a line. The two lines are equally long, yet the different contexts of outwardly or inwardly facing arrows suggest the two lines are quite different from one another. The Gestalt psychologists of the 1920s provided many other examples of how our physiology distorts physical events and relations.

Our learning histories and current environments also influence what we “see” and what we report. In a famous experiment reported in 1951, social psychologist Solomon Asche showed that a person’s report of whether two lines of the type shown in the figure to the right of this commentary were the same or different lengths was strongly influenced by peer reports of the lines’ lengths. If group members, all of whom were confederates of the experimenter, said that a short line was the same length as a long line, subjects were likely to agree with the group’s assessment. The subjects later reported that even though they reported “same” they actually saw differences in the lines’ lengths. The fact remained, however, that the group influenced the report, just as often happens in many human arenas, including science.

Different sub-cultures within science bias (some would say focus) what we “see.” Behavior analysts tend to see contingencies at work when they observe behavior, while Freudian psychanalysts see the same behavior in the context of dynamic forces slugging it out in the mind when they observe the same. Such interpretational differences have led some to go so far as to claim that there is no such thing as an objective observation, that context and culture make a mockery of scientific objectivity.

While, like most extreme positions, this one is overstated, it is does raise the question of objectivity being itself a relative and not an absolute concept. We cannot escape our biases, or at least not all of them. The people we serve as behavior analysts, however, are best helped when we strive toward observations about their behavior and our own that are as free of bias as we can make them.

While, like most extreme positions, this one is overstated, it is does raise the question of objectivity being itself a relative and not an absolute concept. We cannot escape our biases, or at least not all of them. The people we serve as behavior analysts, however, are best helped when we strive toward observations about their behavior and our own that are as free of bias as we can make them.

Behavior analysts spend a long time learning about how to be objective, to step back from bias, in examining both inter-rater (across rater) and intra-rater (within rater across time) reliability data to better ensure we are objective. When you have the opportunity, consider how you see the world and then ask others what they see. And then compare your observations. Find ways to narrow the gaps by using the tools of pinpointing, learning to be specific about what you are seeing, describing in observable ways the words and actions of others. This refinement, moving away from broad terms to describe what you see, is a very good step toward beginning to see your own behavior and that of others more objectively.