Beyond a String around the Finger: Creative Self-Management

A reminder-string around the finger surely wasn’t the first self-management technique, but it may be the best-known (regardless of whether or not anyone really does that anymore). Self-management is figuring out ways for us to control our own behavior - how to solve everyday problems that are obstacles to achieving our goals, being who we want to be, or doing what we want to do with our lives.

You don’t have to be, or even know, a behavior analyst to figure out workable solutions to things about yourself that you would like to change. Now I don’t want to be too cavalier about self-management and imply that anyone can do anything if they set their minds to it, so to speak. I don’t believe that nor should you. There are many problems of living that most of us just can’t handle by ourselves. But, there are many others that many people (not everyone, of course) can and do handle largely on their own. Everything from stopping bad habits - be they trichotillomania (playing with one’s hair constantly), smoking, or even substance abuse - to starting good ones such as weight loss, eating better, getting more exercise, and better work efficiency.

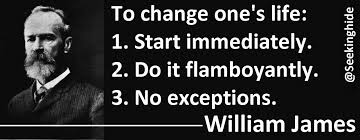

There isn’t space here to detail procedures for setting up a self-help program for specific problems. One of the fathers of American psychology, William James, proposed the 3-part program shown in the illustration accompanying this posting. His are good admonitions, but they may not yield a specific enough plan to help you address your behavior that you might like to change. What follows is a more data-driven three-part program, derived from what we know about how people learn and change. It is at the heart of many successful self-management programs.

There isn’t space here to detail procedures for setting up a self-help program for specific problems. One of the fathers of American psychology, William James, proposed the 3-part program shown in the illustration accompanying this posting. His are good admonitions, but they may not yield a specific enough plan to help you address your behavior that you might like to change. What follows is a more data-driven three-part program, derived from what we know about how people learn and change. It is at the heart of many successful self-management programs.

First, define the behavior to be changed in ways that you or another person can precisely measure it, that is, count it.

First, define the behavior to be changed in ways that you or another person can precisely measure it, that is, count it.

Second, establish a baseline of how often you are engaging in (if it is something you wish to decrease), or not engaging in (if it something you wish to increase). The length of the baseline will vary depending on the type and frequency of the behavior targeted for change.

Second, establish a baseline of how often you are engaging in (if it is something you wish to decrease), or not engaging in (if it something you wish to increase). The length of the baseline will vary depending on the type and frequency of the behavior targeted for change.

Third, arrange consequences - rewards or punishers - for engaging or not engaging in the behavior.

Third, arrange consequences - rewards or punishers - for engaging or not engaging in the behavior.

In this third step, who is to deliver these consequences at appropriate times really requires some consideration. Some contend that you should be able to reward, withhold reward, or even punish your own efforts, but many of us are skeptical of anyone being able to do this reliably, consistently, and, well, objectively. It’s too easy to be soft on yourself when the chips are down (or hidden, along with the dip - if you know where they are we all know what’s gonna happen). Two things can help here (not with the chips ‘n dip, but with delivering consequences). One is to recruit someone else to dispense the rewards according to the program you have set up (preferably someone who is a real drill-sergeant type who knows just when to say “good job” when you have begun to engage in new behavior. Someone who stretches you before delivering the reinforcer — not too far a stretch, but requiring a little more each day as you become more fluent in the behavior. This shaping process helps many people accelerate behavior change over time. Another, even better, solution to delivering reinforcers is to arrange for natural consequences that don’t require you or anyone else to pass out the goodies. Over the long haul, for example, a natural consequence of exercise is feeling good physically and psychologically. It only comes with the activity itself. No one can deliver it for you and the only way you can deliver it yourself is by exercising.

In this third step, who is to deliver these consequences at appropriate times really requires some consideration. Some contend that you should be able to reward, withhold reward, or even punish your own efforts, but many of us are skeptical of anyone being able to do this reliably, consistently, and, well, objectively. It’s too easy to be soft on yourself when the chips are down (or hidden, along with the dip - if you know where they are we all know what’s gonna happen). Two things can help here (not with the chips ‘n dip, but with delivering consequences). One is to recruit someone else to dispense the rewards according to the program you have set up (preferably someone who is a real drill-sergeant type who knows just when to say “good job” when you have begun to engage in new behavior. Someone who stretches you before delivering the reinforcer — not too far a stretch, but requiring a little more each day as you become more fluent in the behavior. This shaping process helps many people accelerate behavior change over time. Another, even better, solution to delivering reinforcers is to arrange for natural consequences that don’t require you or anyone else to pass out the goodies. Over the long haul, for example, a natural consequence of exercise is feeling good physically and psychologically. It only comes with the activity itself. No one can deliver it for you and the only way you can deliver it yourself is by exercising.

The other consideration in delivering consequences is doing so consistently in relation to the behavior, again, something hard to do with one’s self.

Behavior change is hard, no matter who is trying to do it. It often is a case of one step backward for every two forward. But it can be done if one has the tools to do so, and behavior analysis offers those tools to anyone needing them. Like any skill, self-behavior change techniques requires time and patience and work to master. Maybe the first task should be to master the skills of self-management needed to manage your own behavior. Really.

Before starting a self-management program, it’s a good idea to learn as much as you can about them. My good colleague from Aubrey Daniels international, Judy Agnew, earlier this month posted some guidelines on how to keep New Year’s resolutions, which nicely complements this commentary. Her Number 1 suggestion: social support – a child, spouse, parent, BFF, whatever. Let others help you define, measure and arrange consequences appropriately, that’s what a social environment is all about. There are any number of useful "behavioral help" books out there can help you get started. A perineal favorite is one by Watson and Tharp, Self-Directed Behavior: Self-Modification for Personal Adjustment. They have a few ideas that I don’t necessarily agree with (like self-reinforcement), but their advice is sound and systematic.

So, don’t put it off any longer. We all have things we would like to change. Carpe diem!