Stimulus Control and the Avoidance of Evils

When a child learns that asking his mother for money results in getting that valued item and that asking his father does not, it isn’t hard to guess who he’s gonna ask. In out lingo, we say that Mom is an SD (pronounced “ess-dee”), that is, a discriminative stimulus -a stimulus in the presence of which asking is reinforced. Dad, on the other hand, we say is an SΔ ("ess-delta"), a stimulus in the presence of which asking is not reinforced. The astute observer will recognize this as an instance of stimulus control of asking, the moderately sophisticated observer will note that what is going on here is the formation of a discrimination, and the less behaviorally sophisticated observer might even suggest that the child is discriminating between Mom and Dad.

Our astute colleague above got it right in saying that one parent is an SD and the other an SΔ for asking – at least this is how I would label the scenario in the first sentence. I have to point out, though, that stimulus control is something of a misnomer, because the stimuli in the form of Mom and Dad control the response of asking only because they are differentially associated with reinforcement (Mom passes out the cash, Dad does not). If neither or both provided money when asked, asking would occur to neither or both, respectively. That is, Mom and Dad would not differentially control behavior. Stimulus control requires differential reinforcement. The point is that it isn’t the stimulus that really is controlling the behavior, it is the response-reinforcer relation in the context of Mom doling out the cash and Dad not doing so. An important lesson.

Our astute colleague above got it right in saying that one parent is an SD and the other an SΔ for asking – at least this is how I would label the scenario in the first sentence. I have to point out, though, that stimulus control is something of a misnomer, because the stimuli in the form of Mom and Dad control the response of asking only because they are differentially associated with reinforcement (Mom passes out the cash, Dad does not). If neither or both provided money when asked, asking would occur to neither or both, respectively. That is, Mom and Dad would not differentially control behavior. Stimulus control requires differential reinforcement. The point is that it isn’t the stimulus that really is controlling the behavior, it is the response-reinforcer relation in the context of Mom doling out the cash and Dad not doing so. An important lesson.

Why, you may ask, do we need a term like “stimulus control” rather than the older terms of “discrimination” and “generalization” (responding similar to physically different stimuli)? Because stimulus control avoids at least two evils (evils because they distort and misrepresent the ways in which behavior actually is determined) that plague conventional descriptions of this behavioral process

First, discrimination and generalization are quite acceptable so long as they refer to the behavioral process and not to the behaver. Unfortunately, it is oh so easy to slip into the latter description, as did our behaviorally unsophisticated observer in the first paragraph. All of a sudden, he is not speaking of the behavioral process of stimulus differentiation, but of the young man doing the discriminating (or generalizing if he responds similarly to both parents). The behavioral process accountable for by behavior environment relations (read: stimulus control) too easily becomes an instance of the behaver, the young man, being the agent of his or her own behavior. It takes the cause of the behavior out of the environment and puts it inside the person, which is antithetical to a scientific view of behavior.

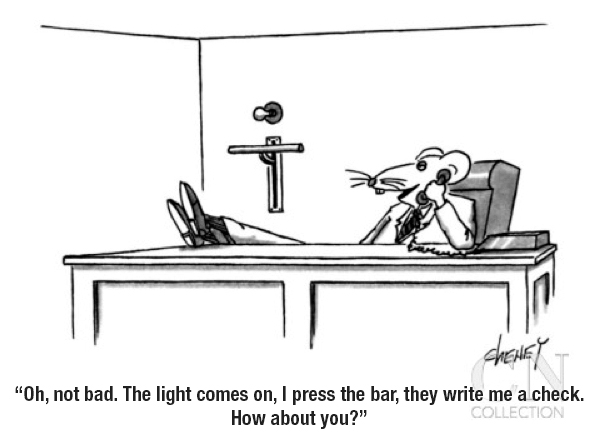

As a second example, consider the cartoon above. Our furry (except for the tail, of course) friend notes that when the light comes on, he presses the lever and gets a check (I doubt that). It is tempting for many to say that the rat is pressing the lever “in order to get paid,” or that our young man is asking “in order to get money.” The cause of pressing and asking in these descriptions is in the future, not in the present. This is teleological. It is like saying that a dropped rock from the hand falls because it is seeking earth, which makes no sense. Stimulus control fixes this. It is the light in the cartoon or Mom in our first example that causes the response and the absence of the light or Dad that causes the response to not occur. When we say the behavior is controlled by the stimulus, the behavior occurs because of something in the here and now, it is not caused by some future reinforcer that exists only the mind’s eye of the rodent or lad.