The Ethics of Reinforcement

Let’s start with the premise that reinforcement is as much a part of the “natural order of things” as is Boyle’s law, Newton’s second law of thermodynamics, or Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. That is, actions in any environment followed by certain kinds of consequences identified as reinforcers are more likely to recur than are actions not followed by those consequences. As part of this natural order of things, it isn’t possible to place ethical value on the principle of reinforcement. It just is the way things work in the natural world.

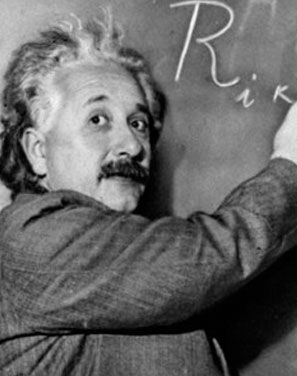

The ethics of scientific principles have been debated for as long as both of these human endeavors have existed. Although the principles themselves are not open to ethical debate – they simply are - the uses to which they are put certainly has been, and should be, debated. Nowhere is this more visible than with the debate that surrounded the ethics of using Einstein’s insights into the nature of the atom, and hence energy, to create nuclear weapons.

The ethics of scientific principles have been debated for as long as both of these human endeavors have existed. Although the principles themselves are not open to ethical debate – they simply are - the uses to which they are put certainly has been, and should be, debated. Nowhere is this more visible than with the debate that surrounded the ethics of using Einstein’s insights into the nature of the atom, and hence energy, to create nuclear weapons.

Using reinforcement does not face ethical scrutiny at the level of nuclear weapons, but there are those who see harnessing the power of reinforcement to change human behavior as both the best and worst of all possible worlds. It is a natural part of almost every human interaction, from learning to read to the most sophisticated and nuanced forms of social interaction. Systematically applying positive reinforcement has allowed people to develop new skills in managing themselves more effectively, whether it is acquiring self-control in areas of concern for the individual to increasing prosocial skills in managing disordered behavior patterns.

Some opposed to its use sometimes note that reinforcement is not always effective in changing behavior. This criticism doesn’t stand up under scrutiny because reinforcement as used by behavior analysis is defined functionally: if something doesn’t make behavior more likely when presented dependent on a response, then that something is not functioning as a reinforcer in the circumstances where it is being used. One of the most basic principle of using reinforcement to change behavior is that you start with something that has been established to be a reinforcer. Rejecting the notion of reinforcement because it doesn’t work means that its definition is not understood by those who say that. If behavior increases, then reinforcement is working. If it does not, it isn’t reinforcement.

Some opposed to its use sometimes note that reinforcement is not always effective in changing behavior. This criticism doesn’t stand up under scrutiny because reinforcement as used by behavior analysis is defined functionally: if something doesn’t make behavior more likely when presented dependent on a response, then that something is not functioning as a reinforcer in the circumstances where it is being used. One of the most basic principle of using reinforcement to change behavior is that you start with something that has been established to be a reinforcer. Rejecting the notion of reinforcement because it doesn’t work means that its definition is not understood by those who say that. If behavior increases, then reinforcement is working. If it does not, it isn’t reinforcement.

Others focus their opposition on extrinsic reinforcement, that is, reinforcers delivered by someone else in visible and tangible ways, because they claim it stifles self-initiating activities and even creativity. These observers suggest that reinforcement should come from the individual “wanting to do” the activity itself, so-called self-generated, intrinsic reinforcement. Two points are worth noting in response to this. First, there are many instances where there is no intrinsic reinforcement in a task or activity for some people. Second, if it were true that extrinsic reinforcement were detrimental to the individual receiving reinforcement, behavior analysts would not advocate its use. The fact is that there is no good evidence that using extrinsic reinforcers stifles anything, as has been suggested in research reviews of intrinsic versus extrinsic reinforcement (e.g., Dickinson, 1989; Eisenberger & Cameron, 1996). There is no valid evidence that shows that reinforcement stifles creativity. Once behavior is established the sources of consequences maintaining it across time and situations are subtle, but reinforcement can be seen as behavior is shaped by its consequences.

Both the behavior of Mother Teresa and Adolph Hitler can be accounted for by reinforcement. The ethics of the behavior of either of these two world figures results from what they did and not because of the behavioral process by which it occurred. Reinforcement has been used to do great good, and probably great bad as well. It is important in evaluating reinforcement to not confuse scientific principle with human actions, intended or unintended consequences, or with the intentions of human involving its use.

Both the behavior of Mother Teresa and Adolph Hitler can be accounted for by reinforcement. The ethics of the behavior of either of these two world figures results from what they did and not because of the behavioral process by which it occurred. Reinforcement has been used to do great good, and probably great bad as well. It is important in evaluating reinforcement to not confuse scientific principle with human actions, intended or unintended consequences, or with the intentions of human involving its use.

References

Dickinson, A. M. (1989). The detrimental effects of extrinsic reinforcement on “intrinsic motivation.” The Behavior Analyst, 12, 1-15.

Eisenberger, R. I., & Cameron, J. (1996). Detrimental effects of reward, American Psychologist, 51, 1123-1136.