Unconditional Positive Regard and Response-Independent Reinforcers

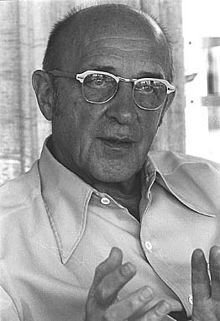

The humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers suggested that a most important feature of human interactions was unconditional positive regard, which is defined as “basic acceptance and support of a person regardless of what the person says or does.” This is an idea which I, a behavior analyst, fundamentally agree. Being a contingency kind of guy, I can quibble over the last part maybe a little, but fundamentally I think that accepting people for “who they are” is a useful approach when it comes to human relationships.

The humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers suggested that a most important feature of human interactions was unconditional positive regard, which is defined as “basic acceptance and support of a person regardless of what the person says or does.” This is an idea which I, a behavior analyst, fundamentally agree. Being a contingency kind of guy, I can quibble over the last part maybe a little, but fundamentally I think that accepting people for “who they are” is a useful approach when it comes to human relationships.

I have a long-standing interest in the effects of reinforcers on behavior delivered independently of responding. Perhaps because of this, I sometimes am asked whether unconditional positive regard doesn’t fly in the face of what we know about reinforcers delivered independently of responding. Such reinforcers can reduce and even eliminate behavior. They are, for example, one of the big bug-a-boos of molecular-minded proponents of treatment integrity who see behavioral chaos lurking behind every reinforcer not accounted for by a preceding response. They also are used frequently to eliminate problem behavior. At the extreme, the argument boils down to if we just basically accept people as they are, that acceptance itself ensures that we will not accidentally and even unintentionally reinforce behavior we should not reinforce.

Note what I just said above about response-independent reinforcers – they reduce and eliminate behavior. It is true that Skinner claimed to have demonstrated superstitious behavior by delivering response-independent food presentations, but (a) the finding is still controversial and (b) because any such behavior is maintained by an adventitious and not a “real” contingency, over the long run it is likely to be unstable and change because there is no required contingency to maintain it. In fact, the latter is exactly what typically happens—remove the response-reinforcer dependency from well-established behavior and over time it heads south, often to near-zero. Of course, both (a) and (b) assume that one’s attention and positive regard are reinforcers, which they may or may not be for the individual to whom they are directed.

Unconditional positive regard doesn’t strike me so much as an event, like we usually think of reinforcers, as a context or antecedent for behavior. It is building or establishing a certain kind of history, creating a broader framework in which responding occurs. Fans of what has been called molar behavior analysis may resonate to this, too. Molar behavior analysis is all about context, usually an extension of behavior in time. Individual reinforcers are less important than the integrative effect of those reinforcers over a larger (admittedly ill-defined) time period. These are the same thing that unconditional positive regard achieves: placing momentary behavior in a larger context and as such I see it as fitting very well with what has been called “humanistic behaviorism.”

How does it fit, though, with the nitty-gritty of, say, managing problem behavior? We’ve all heard the expression “reject the behavior, but not the child.” That’s exactly what I am talking about here: applying and using contingencies- reinforcing appropriate behavior, extinguishing inappropriate behavior – in a context where it is clear the child is loved and accepted as a person. It isn’t the child who is bad or good or dumb or smart, it is the behavior.

How does it fit, though, with the nitty-gritty of, say, managing problem behavior? We’ve all heard the expression “reject the behavior, but not the child.” That’s exactly what I am talking about here: applying and using contingencies- reinforcing appropriate behavior, extinguishing inappropriate behavior – in a context where it is clear the child is loved and accepted as a person. It isn’t the child who is bad or good or dumb or smart, it is the behavior.

No, I haven’t either gone mushy or to the “dark side.” We behavior analysts, or behavioral enviroscientists as I have proposed calling us, have much to teach others about behavior, but we also have a lot to learn by looking to others who describe the world quite differently than do we, and learn from them as a way of making our science even more useful …and widely accepted.