Proactive Accountability for Safety

When incidents occur in business, there is often a call to find those who are responsible and hold them accountable for their actions. Accountability is essential in safety, but the question is, does accountability always have to include negative consequences? In too many cases, accountability translates into disciplinary action against the frontline worker(s) directly tied to the incident (such as verbal and written warnings, suspension, and even termination). If a frontline employee engaged in at-risk behavior that resulted in an incident, you might wonder why discipline is a bad idea. The answer is that incidents are rarely just the result of one employee making a bad choice.

Most incidents are the result of a combination of root causes. While frontline workers are often the ones who engage in the final at-risk behavior, typically multiple upstream at-risk behaviors on the part of management, engineers, and executives contribute as well. A simple example is a frontline employee who fails to put on fall protection when working at height and experiences an injury as a result. On the surface it seems reasonable to blame the worker if he has been trained and clear expectations have been set that fall protection must be used. However, a closer analysis reveals that the fall protection is stored a long distance from the work, and management has put pressure on the employee to compete the task within a short amount of time. In such cases, when the blame is assigned only to the person at the point of the incident, it is, quite simply, unjust. Frontline workers often feel they are blamed for incidents when circumstances beyond their control (but within the control of management) play a part.

Most incidents are the result of a combination of root causes. While frontline workers are often the ones who engage in the final at-risk behavior, typically multiple upstream at-risk behaviors on the part of management, engineers, and executives contribute as well. A simple example is a frontline employee who fails to put on fall protection when working at height and experiences an injury as a result. On the surface it seems reasonable to blame the worker if he has been trained and clear expectations have been set that fall protection must be used. However, a closer analysis reveals that the fall protection is stored a long distance from the work, and management has put pressure on the employee to compete the task within a short amount of time. In such cases, when the blame is assigned only to the person at the point of the incident, it is, quite simply, unjust. Frontline workers often feel they are blamed for incidents when circumstances beyond their control (but within the control of management) play a part.

A system that seems unjust or unfair leads to the erosion of trust and respect between frontline employees and management. Without trust, excellence in safety is unattainable. Safety excellence requires all employees be engaged in proactive safety efforts. Lack of trust, created through unfair disciplinary action (perceived or real), erodes the willingness of people to be more engaged. In the words of one frontline employee, “Why should we do any more than we have to in safety? No matter what we do, management will still blame us when there is an incident.” Without trust, open and honest discussions about at-risk behavior, near misses, and unsafe conditions will never take place. Without those discussions, risk and exposure cannot be minimized.

In addition to undermining trust, there are other reasons to be cautious with the use of discipline and blame. Research shows that negative consequences (like discipline) have detrimental side effects that often outweigh any positive benefit. Some side effects include fear, lower morale, limited engagement, and suppressed reporting of incidents and near misses. Most importantly, discipline often does not result in safety improvement.

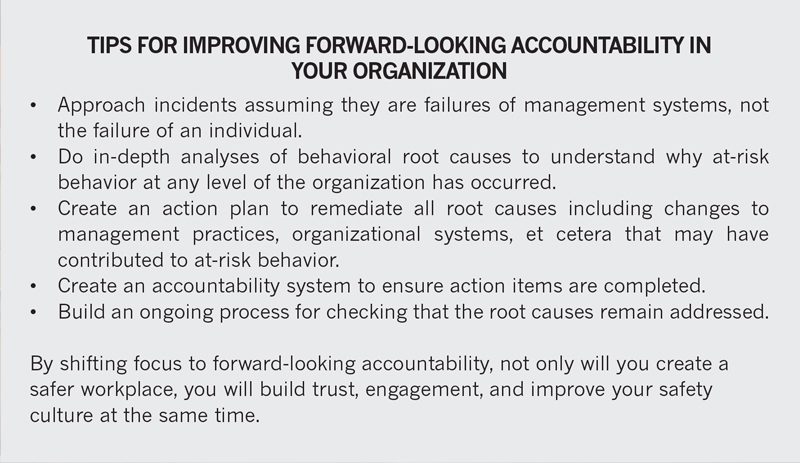

The science of behavior makes this clear; discipline and other negative consequences should be minimized in safety. This doesn’t mean reduced accountability, but a shift in the type of accountability. Virginia Sharpe, in her studies of medical errors and harm, has made an important discrimination between what she calls “forward-looking accountability” and “backward-looking accountability.”[i] Backward-looking accountability is about finding blame, finding the individual who made the mistake, and delivering punishment. As noted previously, there are many downsides to such action, and blaming and punishment seldom results in a safer workplace. According to Sharpe, forward-looking accountability acknowledges the mistake and any harm it caused but, more importantly, it identifies changes that need to be made, and assigns responsibility for making those changes. The accountability is focused around making changes—changing organizational systems, modifying management practices, addressing hazards, and building safe habits—that will prevent a recurrence, not on punishing those who made the mistake. This kind of accountability will positively contribute to building a culture of safety.

To read more about accountability and the use of discipline in safety, read Safe by Accident? Take the Luck out of Safety–Leadership Practices that Build a Sustainable Safety Culture.