Wanted: Safety Accountability from Mining Management

West Virginia’s Upper Big Branch mining disaster on April 5, 2010, the nation’s worst in 40 years, left 29 men dead. As people across the country listened for an explanation, Massey Energy Co. Chairman & CEO Don Blankenship reported that the company’s mines have better safety records than the industry as a whole, with fewer lost-time accidents. Yet we also heard alarming statistics about safety violations piling up and being strongly contested. J. Davitt McAteer, a highly regarded expert in mine safety, notes the number of violations alone as a red flag suggesting the mine should have been closed until the safety issues were resolved. Blankenship counters that if inspectors were seriously worried they would have closed the mine. This begs the question: Is the safety of the miners solely in the hands of the inspectors?

In the background we hear the usual chorus, the mythology that maintains the status quo. “Mining is a dangerous business. Aren’t death and injury to be expected?” and “Isn’t that why miners bring home the big bucks?” However, clearly, many ask: “Isn’t it the job of the company to be alert, to reduce the risk, with or without regulators?” And the answer to this last question is a resounding “Yes.” It is both dangerous and unacceptable for mine leadership to assert that death and injury are an expected part of the job. The utterance of that statement, “as if” death and injury go with the job, is grossly wrong and implies a lack of a clear vision of safety leadership and safety accountability at the highest levels. The assertion of death and injury as a “given” puts solutions at the level of an “act of God,” not man. Leaders who speak of expected injury, let alone death, as givens imply they are helpless to do away with such events. Furthermore, the safety of miners cannot be left solely in the hands of regulators or inspectors. Mine management, at the highest levels, must be held accountable for consequences, intended and unintended, affecting the safety of their employees. Understanding the laws of behavior and applying them in the mines could do much to prevent tragedy, to save lives. Safety leaders across the country take very seriously their unrelenting striving to get to zero, every day. Owners of mines are expected to do the same, not only talking about their commitments, but demonstrating safety first in all they say and do.

Mining: A History of Dangerous Work

With respect to the history of mining and safety assurance, Appalachia generally and West Virginia in particular has a troubling past. “...we are a national sacrifice area,” stated Denise Giardina, a West Virginian stated in a NYT Op ED, April 7, 2010.

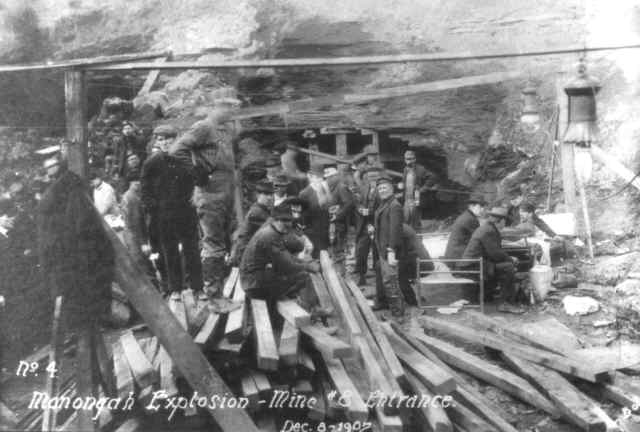

The Monongah Mine Disaster (December 6, 1907) caused the deaths of more than 360 men and boys, and the 1968 Farmington Mine Disaster (another mine with a history of safety problems) killed 78 miners. Both incidents decimated whole communities of mining families in West Virginia, and led to improved regulation of the mining industry. The Sago Mine tragedy and the Aracoma Mine fatalities in 2006 also led to new legislation and regulations. Death and disability from Black Lung, once thought to be all but eradicated, are again on the rise. This is West Virginia’s history. Our miners extract the coal from the earth and out-of-state (for the most part) companies extract the profits. Miners make good wages, and the state benefits some from taxes and related business growth. Miners carry the risk of sudden death, and injury or slow death by lung disease acquired on the job. And “we” continue to settle for the explanation that it is dangerous work.

Granted, that danger has decreased dramatically over the past century. Regulatory mandates and technological advances have contributed to improved safety records in the mining industry as a whole. Yet, when an explosion or cave-in occurs, the same repeated refrains surface: “Mining is an inherently dangerous occupation.” “Accidents happen.”

Today, the technology is readily available to detect methane levels, to use proper ventilation, and to monitor coal dust. At the same time, stopping a mining operation is costly, affecting both profit and wages. If bonus pay is tied to production (without regard to safe procedures) the tendency to ignore safe processes and work around safety devices is predictable based on the laws of behavior. Even when mine management is sincerely concerned about the safety of the workers, the law of unintended consequences flourishes in this fertile ground. Over time, miners and mine leadership will continue with operations even when, for example, methane levels are higher than they should be.

When the focus of mine leadership is almost solely on production, attention is seldom focused on unintended consequences. When production is held up as a key value and is clearly tied to financial success, it is natural for employees to focus on production as the most important part of the job. Safety devices and procedures readily become viewed as time wasters, as being in the way of production, as serving to bring the numbers down.

How does this affect behavior? Let’s look at an example: A continuous miner is a large piece of machinery used in mining. These machines are now equipped with a device to detect methane levels and shut off the machine when it records methane levels above a specified level. As one miner stated, the (human) miner’s objective is to “keep running the coal” and get the pay. To achieve that goal it is possible to create a “bridge” in a continuous miner that effectively disables the automatic shut off device. Why might a miner disable something designed to save his life? Because the majority of the time nothing bad happens when he does and his action allows the mine to keep running. After a while miners who express concerns about high readings are either ignored or ridiculed for being cowards; others begin to doubt the reason for the regulations. Not attending to the readings means that production continues unabated, profits are not adversely affected, wages are maintained, and nothing bad happens (at least not yet). Maybe there really isn’t a need for concern.

The Perfect Storm: A Meeting of Cultures

The miners’ culture of staring death in the face every day (developed over generations of working in the mines and when canaries were the only methane detectors) supports living on the edge without complaint, being there for each other, and keeping the operation going. The wages earned in the mines are unrivaled in the area and the miners understandably don’t want to risk lost wages or lost jobs for themselves or their fellow miners. Miners are also proudly engaged in the important work of making a significant contribution to the nation’s energy reserves. This culture is vulnerable to a corporate culture that focuses on the bottom line, speaks of people over profits but does not translate those words into action, and advocates fighting against the regulators to keep the mine operating under virtually any conditions. In this kind of culture, methane gas, excessive coal dust, and weak roof supports are not the major worry. The inspectors who could find such conditions and fine the company or shut down the mine are the real focus of apprehension. Consequently, considerable corporate effort and energy is devoted to fighting regulation while almost no effort is directed to actually improving the conditions in the mine. When the corporate stance is to work around the rules, postpone needed repairs, and overlook sloppy procedures, most employees will do just that. For example, individual respirators get clogged with coal dust and get left behind on mantrips. Miners place themselves in areas of greatest ventilation so the readings will be good the day the inspector is on hand. “Winning” for the company comes in the form of higher productivity and profit achieved by circumventing the obstacles of regulation.

The miners’ culture of staring death in the face every day (developed over generations of working in the mines and when canaries were the only methane detectors) supports living on the edge without complaint, being there for each other, and keeping the operation going. The wages earned in the mines are unrivaled in the area and the miners understandably don’t want to risk lost wages or lost jobs for themselves or their fellow miners. Miners are also proudly engaged in the important work of making a significant contribution to the nation’s energy reserves. This culture is vulnerable to a corporate culture that focuses on the bottom line, speaks of people over profits but does not translate those words into action, and advocates fighting against the regulators to keep the mine operating under virtually any conditions. In this kind of culture, methane gas, excessive coal dust, and weak roof supports are not the major worry. The inspectors who could find such conditions and fine the company or shut down the mine are the real focus of apprehension. Consequently, considerable corporate effort and energy is devoted to fighting regulation while almost no effort is directed to actually improving the conditions in the mine. When the corporate stance is to work around the rules, postpone needed repairs, and overlook sloppy procedures, most employees will do just that. For example, individual respirators get clogged with coal dust and get left behind on mantrips. Miners place themselves in areas of greatest ventilation so the readings will be good the day the inspector is on hand. “Winning” for the company comes in the form of higher productivity and profit achieved by circumventing the obstacles of regulation.

While many miners experience worry and concern for their safety and that of their fellow miners there may be no trusted route to go with their concerns. It does not take long to learn the difference between what is said and what occurs (companies promote safety on paper or in process and yet punish complainers, in subtle or not-so-subtle ways). In some companies the threat of losing employment is well understood and enough to keep even very worried miners silent. In some situations, suggestions for improvements and complaints about conditions may be met with criticism, ridicule, or simply total inaction. All of these responses are virtually certain to stop miners from expressing their views and sharing their knowledge about conditions in the mine. Until the company begins to reward speaking up about safety concerns, little is likely to change.

The intense effort by some mining companies that goes into fighting or ignoring regulations suggests that further regulation alone is not likely to result in safer practices in all operations. The antecedent of regulation requires the stick of enforcement to have any effect. More importantly, installing safe work practices and maintaining them requires corporate will, a re-prioritization by company management that translates to a safety culture supporting a safe environment and processes as well as individual safe practices.

While clearly there are considerable dangers in the coal mining industry, so much is now known about the dangers and how to mitigate them that it is possible to run a mine without the ever-present threat of disaster so prevalent in the past. In fact many mining companies have relatively few injuries, incidents and safety violations. So why do major incidents leading to death and injury continue to occur?

While clearly there are considerable dangers in the coal mining industry, so much is now known about the dangers and how to mitigate them that it is possible to run a mine without the ever-present threat of disaster so prevalent in the past. In fact many mining companies have relatively few injuries, incidents and safety violations. So why do major incidents leading to death and injury continue to occur?

Two Very Different Ways of Approaching Safety in Coal Mining:

Company A: Production is number one. However, Company A says that safety is number one, even when examination of policies and the behaviors that are rewarded or punished indicate otherwise. Regulation is viewed as the bane of business, something to be fought. Inspectors and regulators are the enemy and war must be waged against them. Almost every cited violation is appealed in court. Though legal battles are expensive, management determines they are less costly than complying with regulations or paying the huge fines that may be levied for not doing so. Some citations are accepted; a few fines are paid and occasionally remedies are made, but the general stance is to view regulation and inspection as an invasion of the Company’s right to work as it sees fit, with its own view of what are safe and unsafe practices. This is, after all, a dangerous business and some level of risk is expected. In fact, it is good to remind the public of this fact often.

Furthermore it is important that the company’s supervisors and foremen understand this. Every time the mine is shut down at the direction of an inspector, production is lost and wages go down. Reporting safety concerns up the chain earns the disdain of fellow miners. Some who report concerns are fired or are considered troublemakers. Over time, those really concerned about safety, those who are free to look elsewhere for work, leave and the workforce becomes more cohesive around keeping many safety concerns to themselves. Internal reports are adjusted to reflect minimal risk. Inspectors are distracted into discussions about minor violations.

Mining is for tough folks—folks who understand risk, folks willing to cut corners to mine a little more coal. Cutting corners, skipping safety steps to increase production, and looking the other way when you see a fellow miner do something unsafe is just part of being a good miner, making sure the wages keep on coming, and making sure you receive your bonus.

The times when disaster did not result from unsafe work practices are frequently called up as evidence to support current and future work behaviors. Accidents are viewed as fate, as low-probability events that cannot be controlled or prevented. After all, this is a dangerous industry and you have to expect that now and then someone will get hurt.

Company B: Safety is core to how this Company is managed. It is a moral imperative to do everything, every day, to ensure the safety of every worker. It is not a changing priority of efficiency or effectiveness like production and quality, but is unchanging and fundamental to how work is done. Production quotas can change from time to time depending on market and other conditions, but the centrality of the safety of each and every worker does not change. It is the constant in this company. Installing and maintaining essential safety measures contribute to a more productive work force. Morale is strong. In this environment, regulation may be viewed as something to exceed. Regulation may represent minimal standards, not the benchmarks Company B strives for. Citations are accepted as (sometimes annoying) opportunities to examine processes and make requested changes as needed, ensuring that they don’t conflict with other safety measures in place. Leadership works with regulators to achieve the best safety environment for employees.

Individual employees engage in those behaviors that serve to keep each other safe. Shortcuts that increase production at the risk of injury are not rewarded. Safer work practices are described, noted, and encouraged. Reporting concerns does not lead to punishment or ridicule. Employees know their concerns will be noted and there will be follow up. Safety records are kept, not only in terms of incidents (results) but with regard to leading indicators; behaviors that minimize risk. Suggestions for risk reduction receive consideration even when not directly related to regulations. Working safely and working productively are not viewed as mutually exclusive. Conditions that raise the level of risk in the workplace are not tolerated.

Decisions made at high levels regarding such things as purchasing, production quotas, budgets, maintenance schedules, and work processes are made in terms of the question: “How will this decision impact safety in this workplace?” Post incident inquiries are conducted thoroughly with the intention of determining root cause and gathering data to ensure the situation does not repeat. Injury and incident will never be viewed as just a part of doing business, as an acceptable derivative of the job.

Company A and Company B above are described as extreme examples but you may not have to look too far to find companies that look very much like Company A as well as companies striving to become Company B. The Company Bs often have relatively high reported incident and lost time rates when they begin to change their culture. Why? Because the data are truer as fear of reporting has been driven out of the workplace. Often times Company As discourage the reporting of lost time injuries and incidents because they don’t want to LOOK bad. Company Bs, on the other hand, know they need to deal with What IS if they are going to improve.

It is time to counter assertions that mining is dangerous and you have to accept a certain amount of death and disaster. You don’t. You must ask the hard questions. You must examine the policies and procedures in place in the mine. You must look at both intended and unintended consequences. Learn about the laws of behavior and how small things can set up a slippery slope of unsafe practice for the wrong reasons. It is time to make a safe day's work more than a hope, but rather, a commitment, actively striven for every day.

The following links are available to those who would like information on this topic.

Mourning in the Mountains, a NY Times op-ed piece, April 7, 2010: www.nytimes.com/2010/04/07/opinion/07giardina.html

Slideshow tour of a Kentucky coal mine with an emphasis on safety: www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2010/04/22/us/0423MINE_13.html

See how safety is applied in a company working always to ensure a safety-first culture and business environment: ?q=fmc-mines-with-safety/