Feedback

On a cold winter’s night, or a hot, humid afternoon, nothing is more reassuring than knowing that my handy-dandy automatic thermostat is on the job keeping my house, and me, at a balmy, even, and comfortable temperature. The idea is simple: a thermometer triggers an electric switch that turns on the heating or cooling (depending on the season), the warming or cooling air feeds back to the thermostat, which then triggers the “off” switch when the set temperature is reached. Look around. These feedback systems – so-called servomechanisms - are at the heart of much of our useful everyday technology, from the cars we drive to the medicines we take.

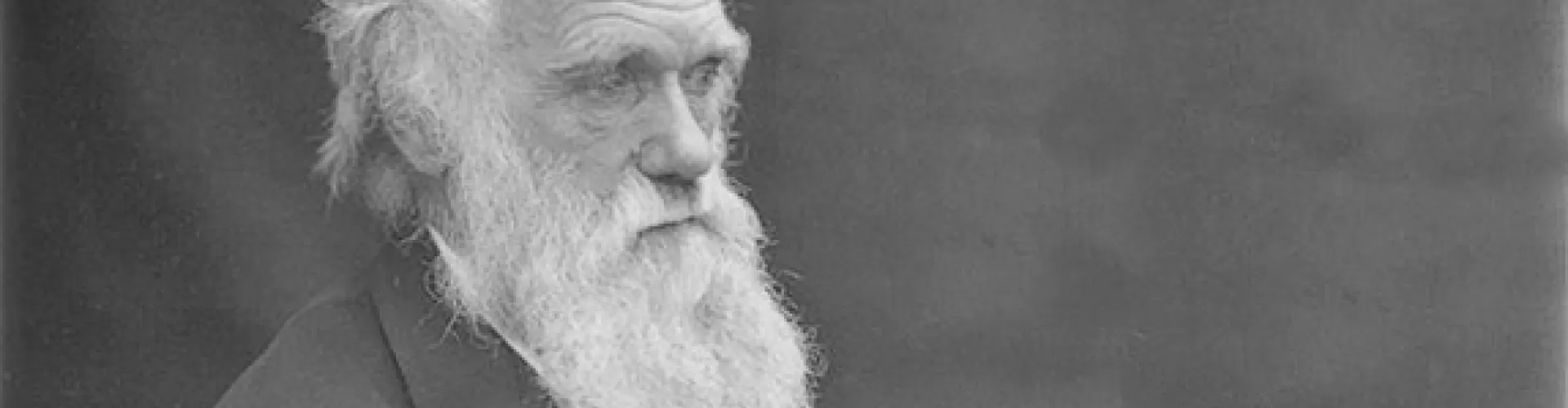

Feedback systems are not restricted to technology. They abound in nature. Perhaps the most brilliant feedback analysis in the history of ideas is Darwin’s theory of natural selection. All of nature was, for Darwin, a huge, interconnected feedback system. Environments and organisms are forever interlocked in a system where changes in one feed back to the other and change it, which in turn feeds back to the other, which in turn ….You get the picture. I have to say it again, Darwin’s analysis was brilliant. It was he who really formalized the idea of feedback systems in the natural environment, which in turn got many other people thinking about feedback in human activity. Now, to be fair, Darwin’s own ideas about feedback in evolving systems may have come from the English pre-industrial revolution environment in which he lived. Watt’s steam engine of the early 1800s, for example, was a feedback system. Even here, there is feedback between developing ideas and changes in the environment in which Darwin lived. So complicated. And at the same time so elegantly simple.

“Feedback" has become part and parcel of our everyday vocabulary, the concept traceable back to Watt and Darwin (and after the 1940s, to Norbert Weiner’s cybernetics). It plays as important a role in the science of behavior as it plays in the science of biology. Beginning in the late 1940s (Moxley, 2001), B. F. Skinner turned to Darwin’s ideas on selectionism as an organizing scheme for his ideas about learning. Learning is all about adaptation – learning how to “get along,” whether it is finding the next meal or dealing with the red-headed bully who lives on the corner. Skinner drew a parallel between the feedback that occurs in natural selection and the feedback that occurs when a particularly attractive young female Cygnus monkey dangling from a tree top works her magic in shaping the behavior of a male of that species such that in the end he achieves the heights needed to be near the object of his desire. The path may be fraught with obstacles, but once learned the lessons apply to the pursuit to other desirable things.

Feedback in everyday use sometimes refers to telling someone something about what they did, without regard to its effect on their future behavior. Used in this way, it is just a label, a name for some interaction with another person. It's called positive or negative depending on what is said (e.g., "that was great" versus "that was stupid"). I would describe its use in this way as a formal or structural use, again, merely a label.

Feedback can be used in another, far more important way by taking into account its behavioral effect. In fact if the feedback has no effect on behavior, is it really even feedback? Doesn't feedback imply a change here just as it does in a heating system? Feedback by its very nature seems functional to me. No matter the form (e.g., written, graphic, oral, or sensory), providing feedback is providing a consequence that is an attempt to influence future behavior. If my “positive feedback” to you makes a repetition of the praised activity more likely in the future, I am reinforcing what you did. “Negative feedback” has the opposite effect on behavior. Whether feedback is labeled positive or negative depends less on what is said than on its effect on future behavior. So the value of what we often label “feedback” typically is only assessed after it has occurred. The assessment of feedback is in terms of its effects on behavior, not on its form or substance. All this is a way of saying that feedback is another way of talking about reinforcement and punishment. Feedback is dependent on a response and it alters the future likelihood of the response. And, as such, it is part of the most important principle that we can apply to change behavior.

Photo: Charles Darwin (1809-1882)