Leaving our Children Behind

There is a great deal of emphasis on testing and outcome in American education circles these days. School systems, individual schools, and individual teachers all have had the onus on them to show that their teaching is effective. Effective is defined in terms of students achieving a pre-established level of performance on standardized tests. Teachers’ and administrators’ pay, with increasing frequency, depends on it.

It is hard to argue with establishing goals and criteria for performance, in this case, the material learned over the course of the academic year. Establishing these goals raises two related questions: Are teachers using what the science of learning has shown to be the most effective teaching methods? Are traditional educational assessment methods up to the task of evaluating either teaching or learning?

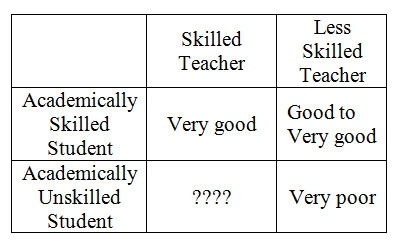

Before I speak to these two issues, it may be helpful to consider children and teachers in the following 2 x 2 matrix, with likely academic outcomes shown in the interior blocks:

A skilled teacher and an academically skilled student are a dynamite combination - a no brainer. Even an academically skilled student in the hands of a less-skilled teacher probably will have a good outcome, because an academically skilled student has other experiences and resources that can compensate for not-so-good to bad teaching. But what about students without the kinds of personal and familial support systems that characterize many academically skilled students? Skilled teachers are more likely to make a difference, but even these teachers don’t always do so; less-skilled teachers, probabilistically speaking, likely are doomed to generally poor outcomes with these less academically skilled children.

With this matrix in mind, let’s move on to educational testing. Educational testing, like much of measurement in the social sciences is based on averages of large numbers of students. Depending on how many of these latter two types of combinations there are in proportion to the total students in the school or system, they will either bring down the average score to the point that the school or system fails to meet its target average score, or, if the achieving children are sufficient in number, the average score will be high enough that the school or system meets its goals and everyone can go home content. Except, or course, the underachieving children who have learned very little or nothing.

The science of behavior emphasizes individual performance for just these reasons. Rather than being satisfied with grouped data, when we implement a learning program, we look for change in every individual relative to their own baseline, not the group’s average. When it comes to affecting educational outcomes, it truly is the individual that matters, not the group average. In this way, truly, no one is left behind.

As for teaching methods, for academically skilled students combined with skilled teachers or even not so good ones, methods may not be that important. Please don’t misunderstand me: I am not saying that they are unimportant, but the difference they make relative to the difference appropriate teaching methods can make with children in my other two groups often is less. The lesson in this from the science of behavior is that we need to pay attention, particularly with less academically skilled children not only to outcome but to the ways in which we present the material to be learned and reward performance. Method does matter. For example, a colleague working with children from underprivileged families in a Headstart environment several years ago successfully taught, during a single school year, five-year olds to not only read, but to read at levels more typical of children several years older. The direct-instruction methods he used are not magic, but science. They use the proven methods of focusing on the individual, breaking the learning task down into small steps, systematically rewarding progress through those small steps, and requiring fluency at a given level before moving on. Also, assessment of progress is not at the end of the year, or even at the end of the day. It is continuous.

This is all well and good, one may say, but the cold hard reality is that any such focused program is expensive, perhaps prohibitively so. I agree, at least as we currently use our educational resources. But maybe there are other ways of teaching. B. F. Skinner in the 1950s and 60s tried to increase efficiency by using instructional programs operated by teaching machines to teach. His machine programs followed the principles outlined above and, in fact, taught basic skills like math and spelling well. The method suffered from technical limitations – it was difficult to create and modify materials and the venues for presenting the materials were almost always linear, not sufficiently allowing for remedial branching in different directions depending on where the learner was having problems. Modern computing offers the possibility of revisiting these types of learning technologies with much greater branching flexibility, visual variety through graphics, and complexity of feedback for responses, to mention just a few. Maybe it is time to revisit these technologies, as well as develop new ones.

This is all well and good, one may say, but the cold hard reality is that any such focused program is expensive, perhaps prohibitively so. I agree, at least as we currently use our educational resources. But maybe there are other ways of teaching. B. F. Skinner in the 1950s and 60s tried to increase efficiency by using instructional programs operated by teaching machines to teach. His machine programs followed the principles outlined above and, in fact, taught basic skills like math and spelling well. The method suffered from technical limitations – it was difficult to create and modify materials and the venues for presenting the materials were almost always linear, not sufficiently allowing for remedial branching in different directions depending on where the learner was having problems. Modern computing offers the possibility of revisiting these types of learning technologies with much greater branching flexibility, visual variety through graphics, and complexity of feedback for responses, to mention just a few. Maybe it is time to revisit these technologies, as well as develop new ones.

Teaching machines and their associated programs are not the only way to go, of course. Everything from the way classrooms are structured to how teachers’ time is allocated to how teaching assistants and student helpers are used should be on the table when we discuss changes to make education happen.

Outcomes are important, certainly. But we can’t achieve the outcomes we want and need in education without greatly expanding our means of reaching them. Conventional teaching methods are not working with many children. Isn’t it time we tried other, proven but (to this point) less widely adopted, approaches to teaching children? Only in so doing can we really have an outcome of no child left behind.