Predicting Future Behavior

It sometimes is said that the best predictor of future behavior is present behavior. Like most blanket, categorical statements about what someone will do next, this one invites some reflection. Taken literally, if a response continues to be reinforced or punished, it might be expected to continue more or less as it has been reinforced. That is, behavior shouldn't change much over time. It, in fact, does change, sometimes to the point that you can’t imagine how it changed so much from its original form. Why?

The statement is based on the idea that reinforcement or punishment make responses, respectively, more or less likely. If a response has been reinforced, then based on this alone we would expect that reinforced response to be more likely in the future. If the response is punished, it would be expected to be less likely in the future. There are several reasons why this direct, rote type of repetition doesn’t occur. To keep things simple, from this point I am going to talk only about reinforcement, but remember that we could make a parallel set of observations about punishment, but with the behavior being less, rather, than more likely once it is punished. Let’s return to the question of why behavior changes, or why present behavior isn’t always the best predictor of future behavior.

Reinforcement has been said to select behavior, much as the environment selects certain physical traits. Such traits often have, or give the possessor, certain advantages in particular environments. Selected behavior presumably similarly gives certain advantages. Just as parents’ traits are blended in their offspring so that the offspring resembles, but is not a clone of, the parents. Behavior replicates, too, although it doesn’t have a Mom and Dad. Given their lineage, these behavioral offspring might be expected to bear family resemblances to their predecessors, but, as with any biological process, they are not likely to be exact replicas. It’s what Skinner called the operant.

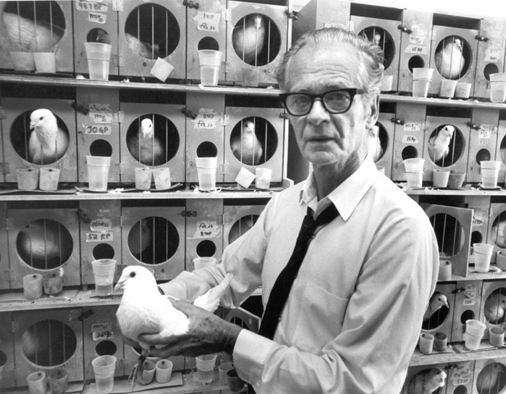

Another consideration is the integrity with which the contingencies are applied. In a famous demonstration, Skinner claimed the development of superstitious behavior when reinforcers were delivered regularly, but independently of what the pigeons he was studying were doing. Each pigeon developed repetitive, stereotyped behavior. My experience is that such behavior drifts over time, so that it may be stable and “predictable” for a while, but over the long haul, because there is no contingency, it is likely to drift from its starting form. Whenever there is a variation in the conditions maintaining the behavior, it is reasonable to expect that the behavior will track these changes. So, the future of some response is constrained by how faithful the continuing conditions are to the conditions under which it was first maintained.

Another consideration is the integrity with which the contingencies are applied. In a famous demonstration, Skinner claimed the development of superstitious behavior when reinforcers were delivered regularly, but independently of what the pigeons he was studying were doing. Each pigeon developed repetitive, stereotyped behavior. My experience is that such behavior drifts over time, so that it may be stable and “predictable” for a while, but over the long haul, because there is no contingency, it is likely to drift from its starting form. Whenever there is a variation in the conditions maintaining the behavior, it is reasonable to expect that the behavior will track these changes. So, the future of some response is constrained by how faithful the continuing conditions are to the conditions under which it was first maintained.

Related to the above is the fact that even if the conditions remain unchanged, the behaver may not always interact with them in the same way. That is, once we set something in place, there is no guarantee that it will operate as intended, which is just my way of saying that we operate in dynamic environments. Even a simple reinforcement schedule like a variable ratio (make N responses, where N varies on each trial, and get a reinforcer after so doing, time after time) interacts with behavior such that the faster I respond, the more quickly I get the reinforcer and the slower I respond the longer is the time between reinforcers. Things are even more complicated, but of the same type, in human social interactions where the behavior of each person affects the behavior of the other. For example, escalating emotional responding, such as often occurs during an argument between two people, is an example of a dynamic behavioral effect of contingencies which the behavior of one person plays off the behavior of the other.

Related to the above is the fact that even if the conditions remain unchanged, the behaver may not always interact with them in the same way. That is, once we set something in place, there is no guarantee that it will operate as intended, which is just my way of saying that we operate in dynamic environments. Even a simple reinforcement schedule like a variable ratio (make N responses, where N varies on each trial, and get a reinforcer after so doing, time after time) interacts with behavior such that the faster I respond, the more quickly I get the reinforcer and the slower I respond the longer is the time between reinforcers. Things are even more complicated, but of the same type, in human social interactions where the behavior of each person affects the behavior of the other. For example, escalating emotional responding, such as often occurs during an argument between two people, is an example of a dynamic behavioral effect of contingencies which the behavior of one person plays off the behavior of the other.

The nature of behavioral selection, contingency dynamics, and the fact that environments change over time all qualify any absolute statements about predicting future behavior based on present behavior. All that said, however, my money is still on present reinforced behavior being the best, albeit imperfect, predictor of what someone will do next, given similar circumstances.