Shaping the Shaper

Shaping is the process whereby we selectively (differentially, for the more technically inclined) reinforce closer and closer approximations to our goal or target behavior to  eventually achieve that target behavior. As I have noted in a previous commentary, “Doing What Comes Naturally: Shaping,” shaping is one of the most ubiquitous of all behavioral phenomena. When we think of shaping, we often imagine a shaper who has in mind a target response and who then proceeds to reinforce successive approximations to it. Consider, for example a child who has a skill deficit in, say, making a certain sound. The shaper knows what the sound should sound like, and provides reinforcement for close and closer approximations to the sound until the child eventually produces the sound as it should sound. This is an accurate description of what happens, but it omits an important element in many instances of shaping that involve people in everyday situations: the behavior of the shaper is not immune to the consequences of his or her attempts to shape the behavior of the shapee.

eventually achieve that target behavior. As I have noted in a previous commentary, “Doing What Comes Naturally: Shaping,” shaping is one of the most ubiquitous of all behavioral phenomena. When we think of shaping, we often imagine a shaper who has in mind a target response and who then proceeds to reinforce successive approximations to it. Consider, for example a child who has a skill deficit in, say, making a certain sound. The shaper knows what the sound should sound like, and provides reinforcement for close and closer approximations to the sound until the child eventually produces the sound as it should sound. This is an accurate description of what happens, but it omits an important element in many instances of shaping that involve people in everyday situations: the behavior of the shaper is not immune to the consequences of his or her attempts to shape the behavior of the shapee.

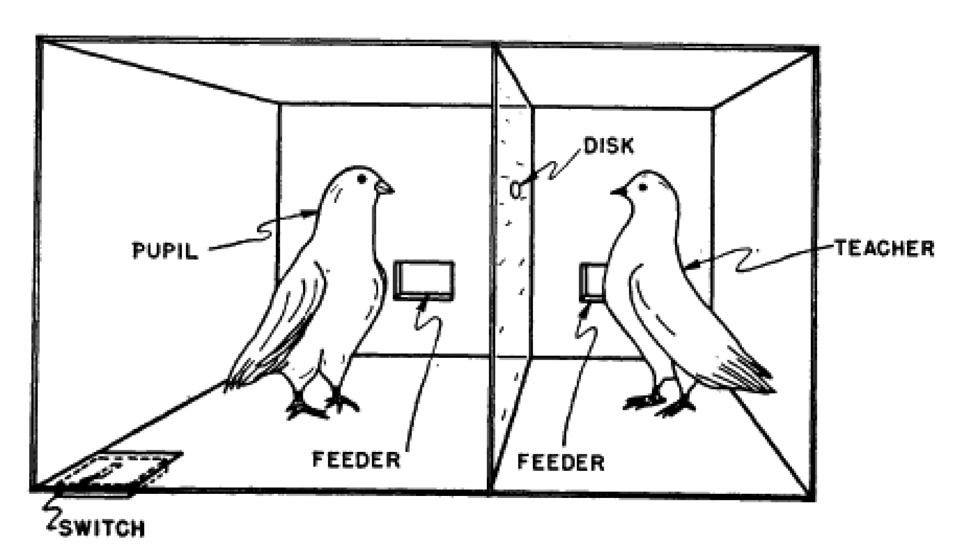

That shaping is a two-way street was elegantly illustrated by a demonstration Richard Herrnstein reported many years ago. The figure below illustrates his arrangement, which was essentially two Skinner boxes located adjacent to one another and separated by a clear plastic wall.

The pigeon in the box on the right was designated the teacher and the one in the box on the left, the pupil. The teacher, in the absence of the pupil, first was taught to peck the plastic disk in its box and then pecking was maintained by occasionally (according to a variable-interval schedule for those familiar with reinforcement schedules). The pupil, in the absence of the teacher, was taught to access food from its feeder. Then, the two pigeons were allowed into their respective chambers at the same time.

The teacher’s pecks subsequently were reinforced only when the pupil was standing on the switch in the southwest corner of the box. For the pupil to be fed, then, it had to be standing on the switch and the teacher had to peck the key. When both of those things happened, both pigeons received food. The behavior of the pupil shape thus controlled the behavior of the teacher by making it more likely the teacher would peck the key when the pupil was standing over the switch. The behavior of the teacher was essential for the pupil, because the teacher would be far more likely to peck when the pupil engaged in the target response. As a result, there was a reciprocal relation for reinforcement for both of the pigeons, a sort of “you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours” arrangement.

Shaping in everyday settings is much like this when two people are involved in the activity. What I as the teacher or manager do affects my students’ or employees’ behavior. What they do affects my behavior. If they are not giving me approximations to the target response, my shaping behavior is not being reinforced and I then have to change my criteria so that they might learn the task (thereby reinforcing my teaching efforts), and if I am not giving them what they need in terms of reinforcement, then their behavior must change to be more in line with my criteria for reinforcement. Whether it is shaping or some other social interaction, relationships are in general are like this: they’re seldom one sided and rather almost always a two-way street, with both parties gaining from one another.