Targeting the Behavioral Stream

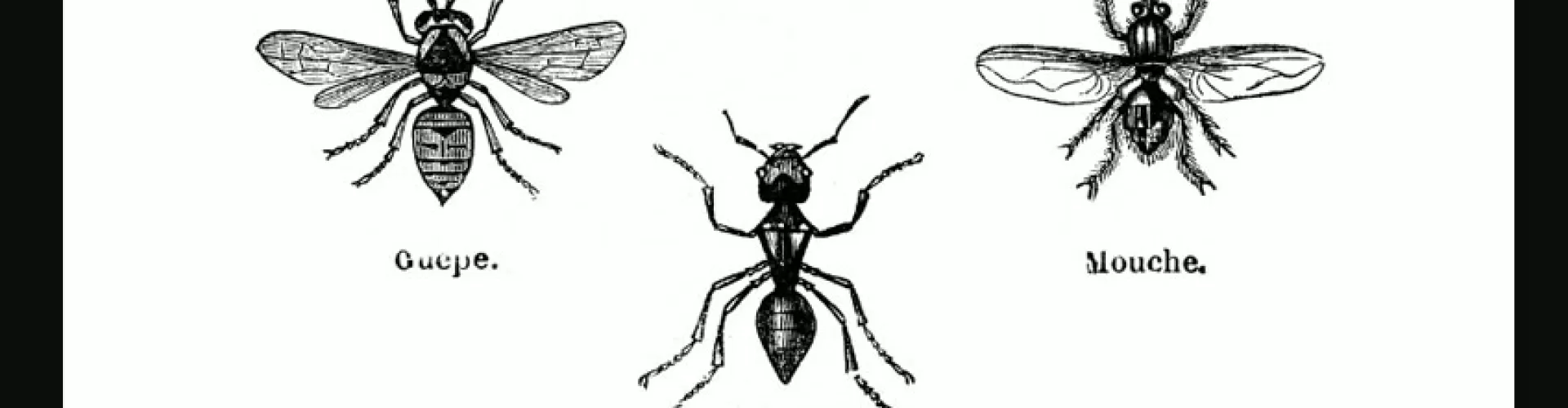

A while ago, I found myself in a lovely restaurant in a small town in Belgium with a close colleague and his wife. We had enjoyed cocktails, a delightful dinner, a bottle of wine, and lots of bottled water, all followed by espressos after the meal. Before leaving for the long ride home, I thought it prudent to visit the men’s room. Looking down into the urinal before me, imagine my surprise when I saw that a small fly had landed inside it. Being a normal red-blooded male, the fly immediately became the target of my “stream.” To my surprise, the fly neither raised an umbrella nor even moved during the deluge that I heaped upon it. After reassembling myself, I made a closer (but not too close) inspection of this stoic beast. The beast was, of course, a fake, a mere porcelain image of a real fly, put there presumably to control just the kind of behavior it controlled in me, and in so doing keep the floors maybe a little cleaner. I’ve since encountered similar targets in other venues, as I am sure have some of my male readers.

A while ago, I found myself in a lovely restaurant in a small town in Belgium with a close colleague and his wife. We had enjoyed cocktails, a delightful dinner, a bottle of wine, and lots of bottled water, all followed by espressos after the meal. Before leaving for the long ride home, I thought it prudent to visit the men’s room. Looking down into the urinal before me, imagine my surprise when I saw that a small fly had landed inside it. Being a normal red-blooded male, the fly immediately became the target of my “stream.” To my surprise, the fly neither raised an umbrella nor even moved during the deluge that I heaped upon it. After reassembling myself, I made a closer (but not too close) inspection of this stoic beast. The beast was, of course, a fake, a mere porcelain image of a real fly, put there presumably to control just the kind of behavior it controlled in me, and in so doing keep the floors maybe a little cleaner. I’ve since encountered similar targets in other venues, as I am sure have some of my male readers.

It turns out there is a science behind my experience.

Many years ago, two psychologists named Paul Brown and Herbert Jenkins were looking for a quick and easy way to train a pigeon to peck a plastic disc used to record responses in learning experiments. Hungry pigeons with no history of ever having pecked the response key were exposed to a simple procedure in which a red light located behind the translucent response key, which was normally dark, occasionally (on average, once a minute or so) was turned on for six seconds, with food delivered at its offset. Several such pairings of the red light with food resulted in many of the pigeons pecking the lit key, even though they had never even seen a key before the session started. This automatic shaping (to learn more about shaping, click here) procedure was dubbed “autoshaping.” Later autoshaping was seen to be an example of a broader class of something called “sign tracking” whereby many species track and respond to certain kinds of stimuli (ever played “catch the laser beam” with a cat?).

Many years ago, two psychologists named Paul Brown and Herbert Jenkins were looking for a quick and easy way to train a pigeon to peck a plastic disc used to record responses in learning experiments. Hungry pigeons with no history of ever having pecked the response key were exposed to a simple procedure in which a red light located behind the translucent response key, which was normally dark, occasionally (on average, once a minute or so) was turned on for six seconds, with food delivered at its offset. Several such pairings of the red light with food resulted in many of the pigeons pecking the lit key, even though they had never even seen a key before the session started. This automatic shaping (to learn more about shaping, click here) procedure was dubbed “autoshaping.” Later autoshaping was seen to be an example of a broader class of something called “sign tracking” whereby many species track and respond to certain kinds of stimuli (ever played “catch the laser beam” with a cat?).

Sometime later, a clever behavior analyst named Ronald K. Siegel suggested that male stream targeting also was an example of sign tracking. Siegel went on to apply the notion of sign tracking to help a 15 year-old adolescent with severe developmental disabilities who had micturition issues, including wetting the toilet seat, floors and walls, and sometimes outside the room containing the toilet. Siegel showed that placing a small (blue) floating target in the toilet essentially eliminated these problems. The problems continued at night until Siegel placed a target in the toilet that was filled with a chemical luminescent material, at which point the problems disappeared at night as well. Siegel went on to implement the same technology on an inpatient ward with nine 9-14 year old males, with similar success.

Sometime later, a clever behavior analyst named Ronald K. Siegel suggested that male stream targeting also was an example of sign tracking. Siegel went on to apply the notion of sign tracking to help a 15 year-old adolescent with severe developmental disabilities who had micturition issues, including wetting the toilet seat, floors and walls, and sometimes outside the room containing the toilet. Siegel showed that placing a small (blue) floating target in the toilet essentially eliminated these problems. The problems continued at night until Siegel placed a target in the toilet that was filled with a chemical luminescent material, at which point the problems disappeared at night as well. Siegel went on to implement the same technology on an inpatient ward with nine 9-14 year old males, with similar success.

Siegel’s solution to what can be a vexing behavior problem for many parents and caregivers is both cost-effective and elegant. It also illustrates how simple technological solutions can be brought to bear on behavioral problems. Now if someone will only come up with an equally easy way to persuade young and old males to raise the toilet seat before honing in on the target!

(To see the full study conducted by Dr. Siegel, click here)