Behavior For The Heart

About 11 years ago, my father underwent successful open-heart surgery at age 74. The surgeons completed a triple by-pass and valve replacement.

My family and I learned that among the many profound risks to cardiac patients post-surgery is depression, combined with a lack of movement. If patients are not up and taking even a few modest steps each day, their chances of successful recovery drop precipitously. One of the earnest prescriptions from his doctors and nurses to each of us, as part of my father’s support network, was that we do everything possible to get him walking and moving every day.

We learned quickly what NOT to do to help my father. First, we learned that although he would get many concerned loved ones who would call and ask him, “How are you feeling?” The question was always met with a very bitter response. “I feel terrible!” Or, “I’m exhausted!” Or, “I want to sleep!” However well intentioned, our efforts to raise his spirits and get him moving were fruitless.

That’s where understanding human behavior comes in. The critical behavior we needed from my dad was for him to get up and get walking every day. We began by changing the antecedents my father was hearing several times each day. We broadcast by email to all loved ones a request to NOT ask my dad how he was feeling. Instead, we told them to ask how many steps he had taken that day. After he had received the third such call, he cast a suspicious glance at me—the only behavior analyst in the room.

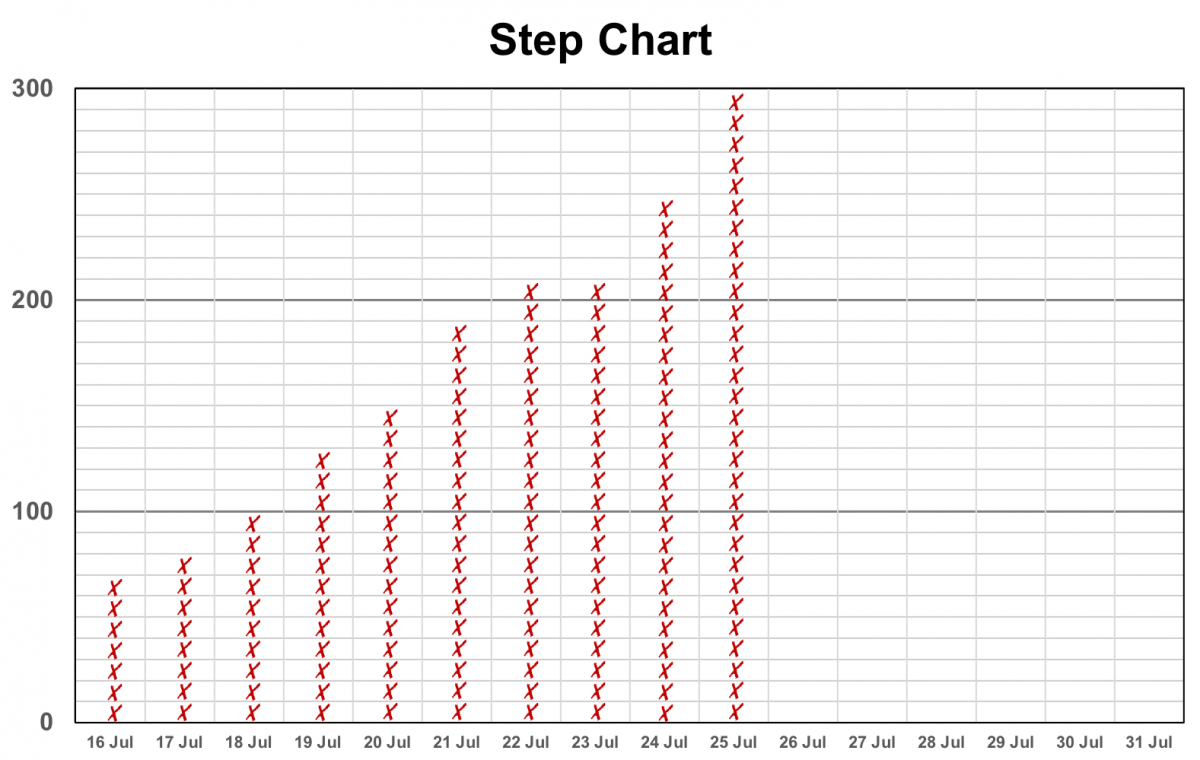

We also knew that antecedents were not enough to sustain his behavior of walking. We had to get some positive consequences in place. T he first was creating a simple step chart for my dad (see Figure). For every 10 steps my dad completed, he could color another cell on the chart. We placed it next to his bed on the wall and attached a marker. As soon as a short trip was completed, it was there waiting for him to update with his data. After a few days, the chart alone was an eye-catching testament to his progress.

he first was creating a simple step chart for my dad (see Figure). For every 10 steps my dad completed, he could color another cell on the chart. We placed it next to his bed on the wall and attached a marker. As soon as a short trip was completed, it was there waiting for him to update with his data. After a few days, the chart alone was an eye-catching testament to his progress.

It also served as an antecedent for doctors and nurses to review his walking data (we took them aside and suggested that they ask him about it each day), in addition to his medical data.

After only a week, my dad would answer the phone by simply declaring how many steps he had completed—before saying anything else! He did so with great pride.

He completed his initial recovery period well ahead of schedule and was cleared to continue his rehab from home. The chart was there waiting for him when he arrived!

He continued updating his step chart every day for a solid 2 years! His walking progressed to the point where he would walk ½ mile every morning with the dog.

His doctors were stunned by his progress, as we all were.

Of course, his recovery was not solely due to the application of behavioral science—there was the excellent work of his cardiologists, surgeons, nursing staff, dieticians, pharmacists, physical therapists, etc. But there really was no medicine that was going to get my dad out of bed and walking every day. And without that, the best medical care in the world may have been for naught.

Even some of the simplest uses of behavioral tools like pinpointing, antecedents, consequences, feedback, and shaping, can have the most profound impact on our lives.