3 Keys to Producing Durable Organizational Change

Benjamin Franklin once said, “When you’re finished changing, you’re finished.” Many organizations seem to embrace this mantra, given the number of continuous improvement initiatives they attempt each year, whether it’s adopting a new data management system, introducing a new organizational process (e.g., a leadership coaching process, Lean Six Sigma, etc.), or changing the organizational culture. If your organization regularly implements continuous improvement change initiatives, you likely have had some push-back in the form of “flavor-of-the-month” complaints or resistance, which arise in the wake of numerous roll-outs, many of which fail to stick. So, why do organizational changes rarely take hold the way we expect them to?

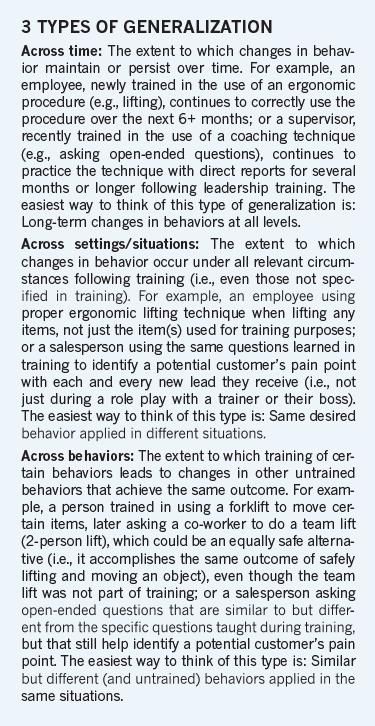

When we talk about organizational change, we’re talking about changing the behavior of the people who work at all levels of the organization, so organizational change requires behavior change of some kind. With any organizational change, there are two big challenges: 1) getting the change started, and 2) keeping the change going. The first challenge, getting the change started, comes with its own unique set of hurdles related to training, organizational culture and other related variables. The second challenge, keeping the change going, is the most difficult yet is critical to sustaining long-term improvements. Jump-starting a new initiative or process in your organization isn’t always easy, but can be accomplished with leaders communicating new expectations, holding kick-off meetings and scheduling training. The more difficult task is maintaining the initial changes after all the fanfare has died down. In other words, how do you get people at all levels to continue demonstrating the critical changes in behavior over time until the changes becomes how you do business moving forward? And beyond simply maintaining the changes over time, there are two additional ways behavior change can be durable: across settings/situations and across behaviors. These three types of change are also referred to as generalization.

Historically, people have assumed that all types of generalization are an automatic byproduct of training or merely set new expectations. Unfortunately this isn’t the case. The safest (and most realistic) approach is to operate as if any generalization following training won’t occur, so don’t expect it. While this may seem counterintuitive, if you know this going in then you can take the necessary steps needed to ensure your training efforts actually stick in the ways you want them to. The truth is, training by itself produces very little long-term impact, although effective coaching given during and particularly after training (e.g., providing opportunities to practice critical behaviors and giving feedback), offers a path forward to achieving all three types of generalization when needed. The good news is that although the tried but ineffective “train and hope” approach often leads to disappointment and frustration, there are strategies you can use to achieve better generalization through effective coaching.

Planning for Generalization

With a focus on the challenge of keeping the change going, we’ll need to make some adjustments to the getting it started piece and, more importantly, to what happens after training. There are three approaches involved in promoting the different types of generalization mentioned above.

- Maximize Reinforcement in the Natural Setting

Stated simply, it’s important that deliberate steps are taken to ensure new behaviors get positively reinforced (R+) sufficiently in the natural environment. If newly acquired behaviors fail to get enough R+, they will stop and the person will likely revert to the previously-used approach. If behaviors aren’t getting R+ out in the real world, one of the culprits may be that the behavior wasn’t trained up to the level needed on the job. Employees, who are shown how to do something once or twice and then released to work independently, whether in an office or a manufacturing setting, rarely have success. Consider whether training the behavior to a higher level of fluency (i.e., where trainees do the behavior correctly and quickly) will facilitate better generalization.

One way to build more R+ into the work environment following training is to make it as easy as possible for people to begin using the new behavior at work. Whatever you can do after training to make people’s initial attempts low on the effort scale (e.g., stage tools where the employee works, have IT place shortcuts to new software systems on the employee’s desktop, use standard work documents in training and real-world settings, etc.) will stack the deck in favor of the different types of generalization. Another source of R+ that can complement making it easy is to ask others in the work setting to look for and positively reinforce generalization when the trainee gets back to work. In other words, try to get peers, supervisors, managers, etc., to provide coaching through feedback and R+ in the work environment. Tapping into many sources of R+ is the key to achieving all three types of generalization because behavior is unlikely to go for extended periods of time with no R+, which we know eventually leads to a complete drop-off in desired behavior.

One way to build more R+ into the work environment following training is to make it as easy as possible for people to begin using the new behavior at work. Whatever you can do after training to make people’s initial attempts low on the effort scale (e.g., stage tools where the employee works, have IT place shortcuts to new software systems on the employee’s desktop, use standard work documents in training and real-world settings, etc.) will stack the deck in favor of the different types of generalization. Another source of R+ that can complement making it easy is to ask others in the work setting to look for and positively reinforce generalization when the trainee gets back to work. In other words, try to get peers, supervisors, managers, etc., to provide coaching through feedback and R+ in the work environment. Tapping into many sources of R+ is the key to achieving all three types of generalization because behavior is unlikely to go for extended periods of time with no R+, which we know eventually leads to a complete drop-off in desired behavior.

- Reinforce Self-Management Skills

One element involved in both training and real-world situations is the employee (at any level). One strategy with a lot of potential is to include the employee directly in achieving successful generalization by teaching and then  reinforcing the use of self-management skills. Self-management has been defined as “the personal application of behavior change tactics that produce a desired change in behavior.”2 While providing extensive details about self-management techniques is beyond the scope of this article, everyone has practiced self-management at one time or another whether at work or home to accomplish certain goals. Self-management techniques include activities such as developing one’s own reminder system or creating to-do lists or step-by-step procedures for certain tasks or behaviors (referred to as antecedents). Another powerful tool for self-management is self-monitoring, in which a person literally observes and records their own behavior(s) (e.g., via a tally, checklist or simply some notes). This can be an effective source of feedback and positive reinforcement for the different types of generalization (think of this as self-coaching). Examples of self-management can be uncovered during coaching conversations, whereby leaders ask their reports questions such as, “What will you do differently to ensure that you try the new approach?” and also during follow-up where leaders may ask coaching questions such as, “How often have you tried the new approach and how did it work?” While leaders and/or trainers are often the initial change agents, over time many people begin to ask themselves the same types of questions to evaluate whether they’re making improvements and to assess the outcomes or consequences for generalization attempts. In other words, once leaders begin asking their reports about the consequences they are experiencing for attempting the change, the reports themselves become vigilant about whether their attempts at using the new behaviors are working better, and working better is R+!

reinforcing the use of self-management skills. Self-management has been defined as “the personal application of behavior change tactics that produce a desired change in behavior.”2 While providing extensive details about self-management techniques is beyond the scope of this article, everyone has practiced self-management at one time or another whether at work or home to accomplish certain goals. Self-management techniques include activities such as developing one’s own reminder system or creating to-do lists or step-by-step procedures for certain tasks or behaviors (referred to as antecedents). Another powerful tool for self-management is self-monitoring, in which a person literally observes and records their own behavior(s) (e.g., via a tally, checklist or simply some notes). This can be an effective source of feedback and positive reinforcement for the different types of generalization (think of this as self-coaching). Examples of self-management can be uncovered during coaching conversations, whereby leaders ask their reports questions such as, “What will you do differently to ensure that you try the new approach?” and also during follow-up where leaders may ask coaching questions such as, “How often have you tried the new approach and how did it work?” While leaders and/or trainers are often the initial change agents, over time many people begin to ask themselves the same types of questions to evaluate whether they’re making improvements and to assess the outcomes or consequences for generalization attempts. In other words, once leaders begin asking their reports about the consequences they are experiencing for attempting the change, the reports themselves become vigilant about whether their attempts at using the new behaviors are working better, and working better is R+!

- Provide Positive Feedback and Reinforcement for Desired Generalization

The three types of generalization represent behaviors that a) persist over time, b) are demonstrated under varying conditions and c) spread to new and relevant behaviors. Because generalization is behavior, and we know that behavior can be positively reinforced and therefore strengthened, it’s vital that any examples of generalization are positively reinforced during subsequent coaching activities, especially people’s early attempts. For example, if trainees begin showing new examples of desired behaviors (e.g., asking new and effective questions to customers), this variability should be reinforced in as many ways as possible to strengthen the use of different forms of the behavior. Or, if a trained behavior is still occurring days, weeks or months after training, that’s an opportunity for a leader to ask how their direct report managed to stay with it over such an extended period of time, and whether the behavior was “working” or possibly has gotten easier to do (all are examples of R+ for the person using the trained behaviors). If a person is observed using a desired behavior in a new situation, the extrapolation itself should be reinforced. When numerous examples of generalized behavior change are reinforced, you’re making it more likely that these examples and new ones will continue.

The three types of generalization represent behaviors that a) persist over time, b) are demonstrated under varying conditions and c) spread to new and relevant behaviors. Because generalization is behavior, and we know that behavior can be positively reinforced and therefore strengthened, it’s vital that any examples of generalization are positively reinforced during subsequent coaching activities, especially people’s early attempts. For example, if trainees begin showing new examples of desired behaviors (e.g., asking new and effective questions to customers), this variability should be reinforced in as many ways as possible to strengthen the use of different forms of the behavior. Or, if a trained behavior is still occurring days, weeks or months after training, that’s an opportunity for a leader to ask how their direct report managed to stay with it over such an extended period of time, and whether the behavior was “working” or possibly has gotten easier to do (all are examples of R+ for the person using the trained behaviors). If a person is observed using a desired behavior in a new situation, the extrapolation itself should be reinforced. When numerous examples of generalized behavior change are reinforced, you’re making it more likely that these examples and new ones will continue.

Generalization Leads to Sustained Change

It’s not uncommon to hear leaders at any level voice their frustration about the failure of training to produce the desired behavior changes back in the workplace, and often the trainee or performer is blamed for the poor outcome. Remember, if behavior changes fail to generalize in any of the ways we want them to, this is expected, which means you cannot tell or train your way to organizational change! In other words, generalization doesn’t naturally occur just because someone is trained in a behavior or task. The good news is there are approaches available to get the desired behavior changes where and when they’re needed, for people and the organizations in which they work, to be successful. While it may be obvious, it’s worth noting that the expectation that generalization occurs, including where and when it occurs, shouldn’t be a secret to the people expected to demonstrate the improvements. Be explicit with people about what behavior changes are desired, provide effective coaching by giving feedback and positive reinforcement when you see good attempts, and recruit as much help as you can to sustain the gain. Only then can you break the vicious cycle of “flavor-of-the-month” initiatives, and achieve meaningful organizational change through better generalization.

It’s not uncommon to hear leaders at any level voice their frustration about the failure of training to produce the desired behavior changes back in the workplace, and often the trainee or performer is blamed for the poor outcome. Remember, if behavior changes fail to generalize in any of the ways we want them to, this is expected, which means you cannot tell or train your way to organizational change! In other words, generalization doesn’t naturally occur just because someone is trained in a behavior or task. The good news is there are approaches available to get the desired behavior changes where and when they’re needed, for people and the organizations in which they work, to be successful. While it may be obvious, it’s worth noting that the expectation that generalization occurs, including where and when it occurs, shouldn’t be a secret to the people expected to demonstrate the improvements. Be explicit with people about what behavior changes are desired, provide effective coaching by giving feedback and positive reinforcement when you see good attempts, and recruit as much help as you can to sustain the gain. Only then can you break the vicious cycle of “flavor-of-the-month” initiatives, and achieve meaningful organizational change through better generalization.

References

- Stokes, T.F., & Baer, D.M. (1977). An implicit technology of generalization. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 10, 349-367.

- Cooper, J.O., Heron, T.E., & Heward, W.L. (2007). Applied behavior analysis (2nd ed.). Columbus, OH: Merrill Prentice Hall.

- Baer, D.M., Wolf, M.M., & Risley, T.R. (1968). Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1, 91-97.

- Osnes, P.G. & Lieblein, T. (2003). An explicit technology of generalization. The Behavior Analyst Today, 3(4), 364-374.